Lecture 18 - Contrastive Learning#

Learning goals#

Understand the idea of contrastive learning.

Construct positive pairs and negative pairs using easy augmentations that mimic lab variability.

Write and inspect a InfoNCE loss with small arrays before touching any model.

Practice designing augmentations for spectra and reaction conditions.

1. Setup#

2. Contrastive learning concepts#

Why contrastive learning?

In many lab projects, positive results are rare and negatives are mixed with non-attempts.

Contrastive learning can pretrain an embedding using instance agreement without needing full labels, then a small labeled set can train a light classifier on top.

The basic objective is simple: samples that are different views of the same underlying item should be close in the embedding, while different items should be far.

A view can be a small transformation that preserves identity.

In chemistry we can mimic instrument noise, baseline drift, slight temperature jitter, or solvent variations that do not change the label of interest.

We will keep the math light and the code step-by-step.

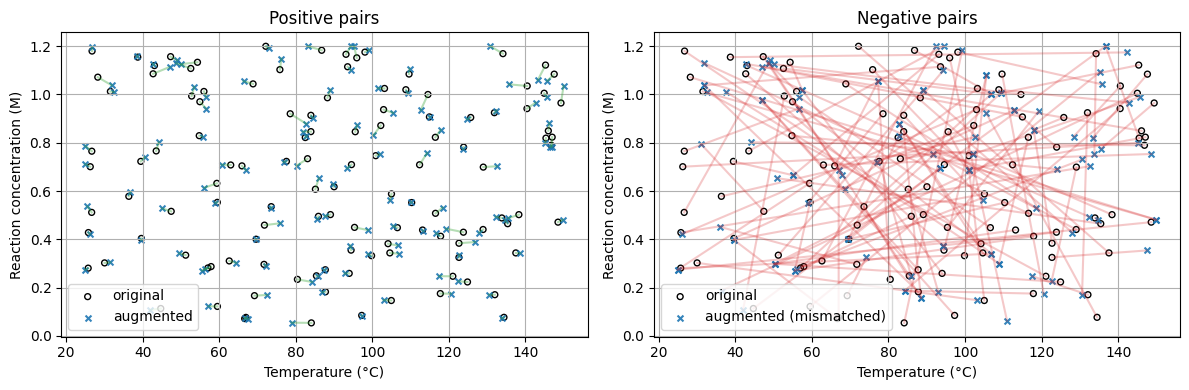

2.1 What is a positive pair and a negative pair#

Positive pair: two views of the same experiment or the same molecule.

Negative pair: two views that come from different experiments or different molecules.

Example labels for a toy case:

An experiment that yields the product with high purity.

Two instruments that read the same sample but with slight noise.

These two readings form a positive pair. Two readings from different samples form a negative pair.

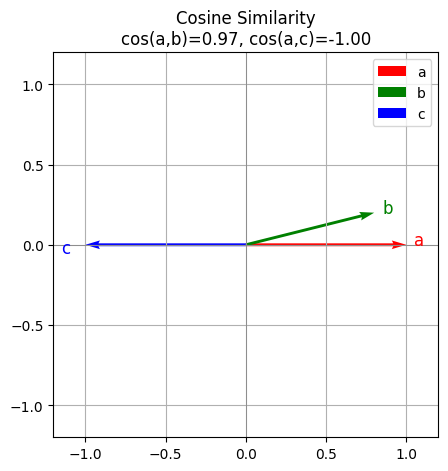

2.2 Cosine similarity#

Cosine similarity measures the angle between vectors. It is large when vectors point in the same direction.

\( \operatorname{cos\_sim}(u,v)=\frac{u\cdot v}{\|u\|\,\|v\|} \)

We use it because the magnitude is not as important as the direction in many embedding spaces.

# Cosine similarity in NumPy

def cos_sim(u, v, eps=1e-8):

u = np.asarray(u, dtype=float)

v = np.asarray(v, dtype=float)

num = np.dot(u, v)

den = np.linalg.norm(u) * np.linalg.norm(v) + eps

return float(num / den)

a = np.array([1.0, 0.0])

b = np.array([0.8, 0.2])

c = np.array([-1.0, 0.0])

print("cos(a,b) =", cos_sim(a,b))

print("cos(a,c) =", cos_sim(a,c))

cos(a,b) = 0.970142488380626

cos(a,c) = -0.9999999900000002

Below is the verctor visualization. You can see a b are similar to each other which a c are very different (opposite).

3. Contrastive learning in chemistry#

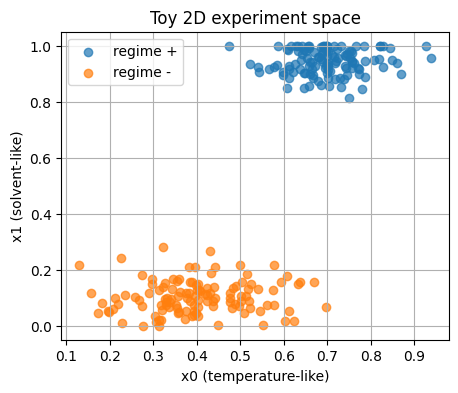

We simulate two experiment classes.

Think of them as two reaction regimes.

Each point is a pair of features:

\(x_0\) behaves like a normalized temperature.

\(x_1\) behaves like a solvent family flag that you can think of as 0 or 1 with small jitter for plotting.

# 2D toy dataset with two regimes

n_pos = 120

n_neg = 120

x_pos = np.column_stack([

rng.normal(0.70, 0.08, n_pos),

np.clip(rng.normal(0.95, 0.05, n_pos), 0.0, 1.0)

])

x_neg = np.column_stack([

rng.normal(0.40, 0.10, n_neg),

np.clip(rng.normal(0.10, 0.06, n_neg), 0.0, 1.0)

])

X = np.vstack([x_pos, x_neg]).astype(np.float32)

y = np.hstack([np.ones(n_pos, dtype=int), np.zeros(n_neg, dtype=int)])

show_shape("X", X)

head(X, name="X")

X.shape: (240, 2)

X head:

[[0.6654 0.9177]

[0.6096 0.9834]

[0.7539 0.981 ]]

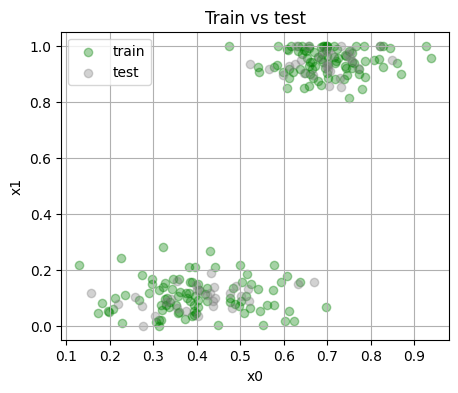

3.2 Simple train and test split#

We keep a fixed split for repeatability.

Train size: 180 Test size: 60

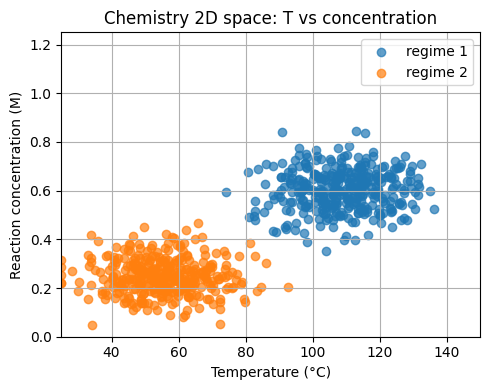

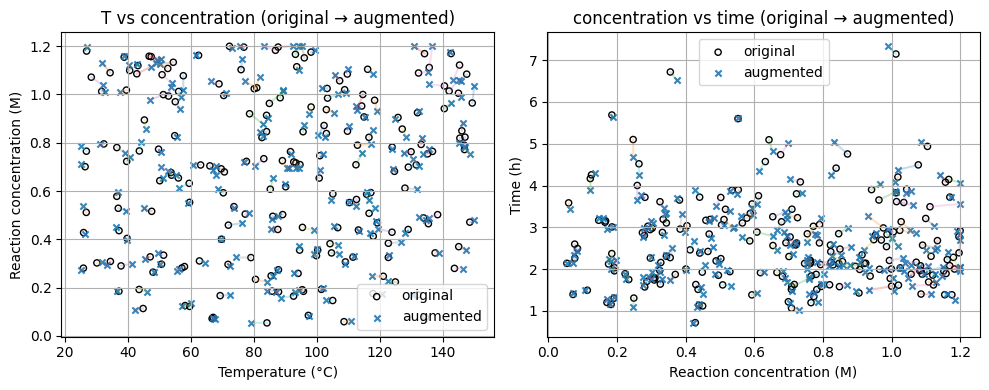

Now, let’s keep the spirit of the 2D toy example but uses chemistry units.

Feature 1: temperature

T_Cin the range 25 to 150 °C.Feature 2: reaction concentration

conc_Min molar units.

We form two regimes for a toy yield label.

# Chemistry-calibrated 2D dataset

n_pos2 = 350

n_neg2 = 350

T_pos = np.clip(rng.normal(110.0, 12.0, n_pos2), 25, 150)

C_pos = np.clip(rng.normal(0.60, 0.08, n_pos2), 0.05, 1.20)

T_neg = np.clip(rng.normal(55.0, 12.0, n_neg2), 25, 150)

C_neg = np.clip(rng.normal(0.25, 0.07, n_neg2), 0.05, 1.20)

X_chem2d = np.vstack([

np.column_stack([T_pos, C_pos]),

np.column_stack([T_neg, C_neg])

]).astype(np.float32)

y_chem2d = np.hstack([

np.ones(n_pos2, dtype=int),

np.zeros(n_neg2, dtype=int)

])

chem2d_df = pd.DataFrame({"T_C": X_chem2d[:,0], "conc_M": X_chem2d[:,1], "label": y_chem2d})

show_shape("X_chem2d", X_chem2d)

chem2d_df.head()

X_chem2d.shape: (700, 2)

| T_C | conc_M | label | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 93.191246 | 0.554962 | 1 |

| 1 | 98.001747 | 0.535892 | 1 |

| 2 | 106.118027 | 0.533380 | 1 |

| 3 | 86.066620 | 0.708883 | 1 |

| 4 | 85.482567 | 0.513050 | 1 |

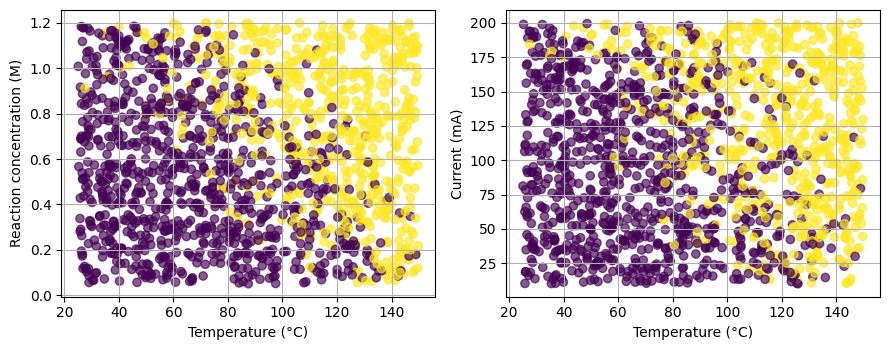

3.4 Add current and time#

We extend the features to [T_C, conc_M, current_mA, time_h] and synthesize a label that is more graded.

X_chem4d.shape: (1500, 4)

| T_C | conc_M | current_mA | time_h | score | prob | label | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 49.805883 | 0.600655 | 40.833851 | 2.157691 | -2.208944 | 0.098950 | 0 |

| 1 | 126.562416 | 0.211544 | 72.354625 | 2.702346 | -0.678296 | 0.336642 | 0 |

| 2 | 82.568180 | 0.127770 | 152.062647 | 3.505866 | -0.606200 | 0.352927 | 0 |

| 3 | 48.536913 | 1.035117 | 30.949824 | 2.568091 | -1.294756 | 0.215049 | 0 |

| 4 | 49.894593 | 0.263611 | 50.120879 | 4.105867 | -2.681535 | 0.064072 | 0 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 1495 | 65.210976 | 1.024820 | 45.167810 | 1.961686 | 0.079109 | 0.519767 | 0 |

| 1496 | 106.716612 | 0.277887 | 57.055591 | 3.015707 | -0.769024 | 0.316690 | 0 |

| 1497 | 58.082437 | 0.125463 | 19.037200 | 4.255520 | -2.833547 | 0.055538 | 0 |

| 1498 | 100.070791 | 0.840978 | 105.132453 | 2.283671 | 0.285704 | 0.570944 | 1 |

| 1499 | 56.201787 | 0.140920 | 67.082359 | 1.929128 | -2.718778 | 0.061874 | 0 |

1500 rows × 7 columns

As you can see here (and we have been seen similar cases many times this semester), when we go into high dimensional space with more and more reaction parameters, classification become challenging. In the previous lectures, we have many molecular descriptors, and now we have too many reaction parameters.

4. Building positive and negative pairs with easy augmentations#

Contrastive learning needs pairs.

We will define augmentations that keep the identity of the same sample.

These are small changes that simulate instrument noise or small condition jitter.

4.1 Augmentations for the toy 2D data#

def jitter(x, noise_std=0.02):

x = np.asarray(x, dtype=float)

return x + rng.normal(0.0, noise_std, size=x.shape)

def small_rotation(x, angle_std_deg=8.0):

# Rotate 2D point around origin by a small random angle in degrees

theta = np.deg2rad(rng.normal(0.0, angle_std_deg))

R = np.array([[np.cos(theta), -np.sin(theta)],

[np.sin(theta), np.cos(theta)]])

return (R @ x.reshape(2,1)).ravel()

def clip01(x):

return np.clip(x, 0.0, 1.0)

def augment_view(x):

# One simple pipeline: jitter then a tiny rotation, then clip to [0,1]

return clip01(small_rotation(jitter(x, 0.02), 6.0))

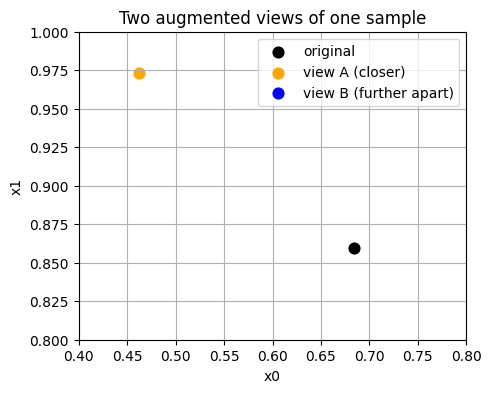

# Show one point and two views

x0 = X_train[0]

v1 = augment_view(x0)

v2 = augment_view(x0)

print("Original:", x0)

print("View A :", v1)

print("View B :", v2)

Original: [0.6845 0.8594]

View A : [0.4622 0.9731]

View B : [0.8054 0.773 ]

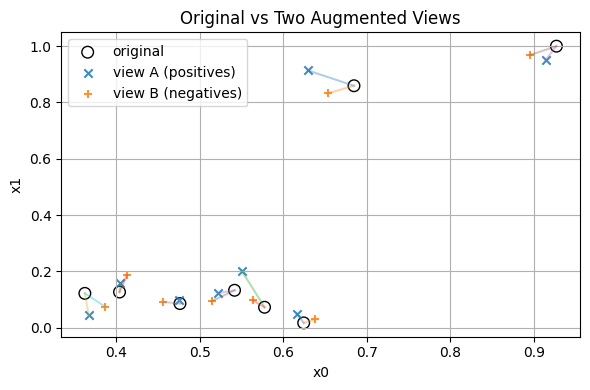

4.2 Build a small batch of pairs#

We now collect a tiny batch from the training set for demonstration.

We will keep it small to print everything clearly.

What counts as a negative here

For a given anchor in view A, all other items in view B act as negatives.

We do not need explicit negative labels, the batch itself supplies them.

4.3 Augmentations for chemistry conditions#

We now design a view function for the 4D chemistry conditions.

The function applies small jitters and clips to the physical bounds.

We also view changes step by step.

def augment_conditions_stepwise(v, T_std=2.0, c_rel=0.03, i_std=5.0, time_rel=0.05,

bounds=((25,150),(0.05,1.20),(10,200),(0.2,8.0))):

v = np.array(v, dtype=float)

T, c, i, t = v

# Step 1: temperature jitter

T1 = T + rng.normal(0.0, T_std)

# Step 2: relative concentration change

c1 = c * (1.0 + rng.normal(0.0, c_rel))

# Step 3: current jitter

i1 = i + rng.normal(0.0, i_std)

# Step 4: time relative jitter

t1 = t * (1.0 + rng.normal(0.0, time_rel))

# Step 5: clip

(Tmin, Tmax), (cmin, cmax), (imin, imax), (tmin, tmax) = bounds

out = np.array([

np.clip(T1, Tmin, Tmax),

np.clip(c1, cmin, cmax),

np.clip(i1, imin, imax),

np.clip(t1, tmin, tmax)

])

steps = {

"original": v,

"after_T": np.array([T1, c, i, t]),

"after_conc": np.array([T1, c1, i, t]),

"after_current": np.array([T1, c1, i1, t]),

"after_time": np.array([T1, c1, i1, t1]),

"clipped": out,

}

return out, steps

# Pick one sample and visualize the steps

sample_idx = 5

v0 = X_chem4d[sample_idx]

v1, steps = augment_conditions_stepwise(v0)

print("Original:", v0)

for k in ["after_T","after_conc","after_current","after_time","clipped"]:

print(f"{k:>13}:", np.round(steps[k], 3))

Original: [78.447 0.4713 82.1547 2.013 ]

after_T: [76.087 0.471 82.155 2.013]

after_conc: [76.087 0.466 82.155 2.013]

after_current: [76.087 0.466 80.534 2.013]

after_time: [76.087 0.466 80.534 2.029]

clipped: [76.087 0.466 80.534 2.029]

Labeling Pairs

Positive pair = an original with its own augmented version.

Negative pair = an original with an augmented point from a different row.

Pairs matrix shapes: (240, 4) (240, 4) (240,)

Example rows:

y=1 orig=[83.973 0.846 45.915 2.133] pair=[81.87 0.846 38.295 2.078]

y=1 orig=[89.086 0.502 39.465 2.249] pair=[87.673 0.496 38.113 2.126]

y=1 orig=[ 56.027 1.012 133.294 7.148] pair=[ 56.635 0.99 137.152 7.336]

With data augmentation, without doing any new experiments, we “create” labels by pairing.#

5. InfoNCE loss step-by-step#

5. InfoNCE loss step-by-step#

The InfoNCE loss is a core objective in contrastive learning. It makes embeddings of positive pairs (two augmentations of the same input) close, and negative pairs (different samples) far apart.

Step 1: Normalize the embeddings

Given two batches of embeddings \(x_a\) and \(x_b\) of shape \(N \times d\), normalize them along the feature dimension:

\( \tilde{x}_a = \frac{x_a}{\|x_a\|_2}, \quad \tilde{x}_b = \frac{x_b}{\|x_b\|_2} \)

This ensures that cosine similarity equals the dot product.

Step 2: Compute the similarity matrix

The cosine similarity between samples is:

\( S_{ij} = \tilde{x}_{a,i} \cdot \tilde{x}_{b,j} \)

\(S_{ii}\) → positive pair (same sample, two augmentations)

\(S_{ij}\) for \(i \ne j\) → negative pairs (different samples)

Step 3: Apply temperature scaling

A temperature parameter \(\tau\) sharpens or softens similarity scores:

\( \text{logits}_{ij} = \frac{S_{ij}}{\tau} \)

A smaller \(\tau\) (e.g., \(0.1\)) increases contrast between pairs.

Step 4: Compute the InfoNCE loss

For each sample \(i\):

\( \ell_i = -\log \frac{\exp(S_{ii} / \tau)}{\sum_{j=1}^{N} \exp(S_{ij} / \tau)} \)

The overall loss:

\( \mathcal{L}_{\text{InfoNCE}} = \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^{N} \ell_i \)

Intuitively, the numerator measures similarity of the correct positive pair,

and the denominator sums over all possible pairs, acting like a softmax classifier.

Here is a numerical example (2D, 3 Samples) for you to understand this process:

Let \(N=3\) and each embedding have 2 dimensions:

\( x_a = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 \\ 1 & 1 \end{bmatrix}, \quad x_b = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 1 \\ 1 & -1 \\ 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix} \)

Normalize each row:

\( \|x_a\| = \begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ 1 \\ \sqrt{2} \end{bmatrix}, \quad \|x_b\| = \begin{bmatrix} \sqrt{2} \\ \sqrt{2} \\ 1 \end{bmatrix} \)

\( \tilde{x}_a = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 \\ 0.707 & 0.707 \end{bmatrix}, \quad \tilde{x}_b = \begin{bmatrix} 0.707 & 0.707 \\ 0.707 & -0.707 \\ 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix} \)

Compute similarity matrix \(S = \tilde{x}_a \tilde{x}_b^T\)

\( S = \begin{bmatrix} 0.707 & 0.707 & 0.0 \\ 0.707 & -0.707 & 1.0 \\ 0.999 & 0.0 & 0.707 \end{bmatrix} \)

Apply temperature \(\tau = 0.2\)

\( \text{logits} = \frac{S}{0.2} \)

Compute loss for sample \(i=1\)

\( \ell_1 = -\log \frac{\exp(0.707 / 0.2)}{\exp(0.707 / 0.2) + \exp(0.707 / 0.2) + \exp(0 / 0.2)} \)

\( \exp(0.707 / 0.2) = e^{3.535} \approx 34.3, \quad \exp(0) = 1 \)

\( \ell_1 = -\log\frac{34.3}{34.3 + 34.3 + 1} = -\log(0.494) \approx 0.706 \)

You can repeat for \(i=2\) and \(i=3\), then average to get:

\( \mathcal{L}_{\text{InfoNCE}} = \frac{1}{3} (\ell_1 + \ell_2 + \ell_3) \)

Finally, we need to normalize and compute pairwise cosine similarities.

The encoder network is not required yet.

We only take the two views xa and xb2, normalize them, then compute a similarity matrix.

def l2_normalize_rows(M, eps=1e-9):

M = np.asarray(M, dtype=float)

norms = np.linalg.norm(M, axis=1, keepdims=True) + eps

return M / norms

za = l2_normalize_rows(xa) # embeddings for view A

zb = l2_normalize_rows(xb2) # embeddings for view B

# Pairwise cosine similarities S[i,j] = za[i] dot zb[j]

S = za @ zb.T

show_shape("za", za)

show_shape("zb", zb)

show_shape("S", S)

print("First 3x3 block of S:\n", S[:3,:3])

za.shape: (8, 2)

zb.shape: (8, 2)

S.shape: (8, 8)

First 3x3 block of S:

[[0.9981 0.8564 0.706 ]

[0.8601 0.9985 0.982 ]

[0.7814 0.9814 0.9987]]

Note

Row i and column i correspond to the positive pair for item i.

Large diagonal values are good for this loss.

5.2 InfoNCE with a temperature scalar#

We use a small positive constant tau that controls the softness of the softmax.

Smaller tau makes the softmax sharper.

The per-item loss with positive at index i is:

\( \ell_i = -\log \frac{\exp(S_{ii}/\tau)}{\sum_{j=1}^N \exp(S_{ij}/\tau)} \)

The batch loss is the mean of \(\ell_i\).

def info_nce_from_sim(S, tau=0.1):

# S is an NxN similarity matrix between view A rows and view B rows

N = S.shape[0]

logits = S / tau

# subtract max per row for numerical stability

logits = logits - logits.max(axis=1, keepdims=True)

exp_logits = np.exp(logits)

denom = exp_logits.sum(axis=1, keepdims=True)

prob_pos = exp_logits[np.arange(N), np.arange(N)] / denom.ravel()

loss = -np.log(np.clip(prob_pos, 1e-12, 1.0)).mean()

return float(loss), prob_pos

loss_val, ppos = info_nce_from_sim(S, tau=0.1)

print("InfoNCE loss:", round(loss_val, 4))

print("Prob of positive pair per item:", np.round(ppos, 4))

InfoNCE loss: 1.5839

Prob of positive pair per item: [0.4156 0.1772 0.1667 0.1692 0.1723 0.1825 0.1506 0.3194]

5.3 Symmetric loss#

Often we also compute the reverse direction by swapping the roles of A and B, then average the two losses.

This can improve stability.

loss_ab, _ = info_nce_from_sim(za @ zb.T, tau=0.1)

loss_ba, _ = info_nce_from_sim(zb @ za.T, tau=0.1)

print("AB direction loss:", round(loss_ab, 4))

print("BA direction loss:", round(loss_ba, 4))

print("Symmetric loss:", round((loss_ab + loss_ba)/2.0, 4))

AB direction loss: 1.5839

BA direction loss: 1.5919

Symmetric loss: 1.5879

Tip

When debugging a new contrastive implementation, start with very small batches and print the intermediate arrays.

You can catch indexing mistakes with human eyes before moving to larger experiments.

5.4 Tiny encoder for contrastive learning#

With torch installed, we fit a small encoder that maps 2D inputs to a 2D embedding and uses InfoNCE.

The goal is to see the points cluster by identity.

6.1 Define a simple dataset and encoder#

if torch is not None:

class PairDataset(Dataset):

def __init__(self, X_array, aug_fn, n_items=240):

self.X = np.asarray(X_array, dtype=np.float32)

self.aug_fn = aug_fn

self.n_items = min(n_items, len(self.X))

def __len__(self):

return self.n_items

def __getitem__(self, idx):

x = self.X[idx]

v1 = self.aug_fn(x)

v2 = self.aug_fn(x)

return v1.astype(np.float32), v2.astype(np.float32)

class TinyEncoder(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, in_dim=2, out_dim=2, hidden=32):

super().__init__()

self.net = nn.Sequential(

nn.Linear(in_dim, hidden),

nn.ReLU(),

nn.Linear(hidden, out_dim),

)

def forward(self, x):

z = self.net(x)

z = F.normalize(z, p=2, dim=1)

return z

We compute the pairwise similarities, then the loss, then one optimizer step.

We print shapes to keep it clear.

if torch is not None:

ds = PairDataset(X_train, augment_view, n_items=len(X_train))

dl = DataLoader(ds, batch_size=64, shuffle=True)

enc = TinyEncoder(in_dim=2, out_dim=2, hidden=32)

opt = torch.optim.Adam(enc.parameters(), lr=1e-2)

xb_a, xb_b = next(iter(dl))

show_shape("xb_a torch", xb_a)

show_shape("xb_b torch", xb_b)

enc.train()

z_a = enc(xb_a)

z_b = enc(xb_b)

show_shape("z_a", z_a)

show_shape("z_b", z_b)

# Similarity matrix

S = z_a @ z_b.T

tau = 0.1

logits = S / tau

logits = logits - logits.max(dim=1, keepdim=True).values

exp_logits = torch.exp(logits)

prob_pos = torch.diag(exp_logits) / exp_logits.sum(dim=1)

loss = -torch.log(torch.clamp(prob_pos, min=1e-12)).mean()

print("Loss (one step):", float(loss.item()))

xb_a torch.shape: torch.Size([64, 2])

xb_b torch.shape: torch.Size([64, 2])

z_a.shape: torch.Size([64, 2])

z_b.shape: torch.Size([64, 2])

Loss (one step): 3.4214134216308594

if torch is not None:

# Backprop once

opt.zero_grad(set_to_none=True)

loss.backward()

opt.step()

print("Step done.")

Step done.

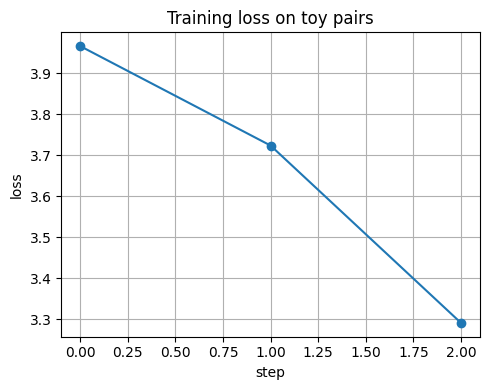

We split the loop across two cells to keep each piece small.

First we define the function that computes batch loss.

Then we run a tiny loop and record losses for a simple plot.

if torch is not None:

def batch_info_nce(encoder, xb_a, xb_b, tau=0.1):

z_a = encoder(xb_a)

z_b = encoder(xb_b)

S = z_a @ z_b.T

logits = S / tau

logits = logits - logits.max(dim=1, keepdim=True).values

exp_logits = torch.exp(logits)

denom = exp_logits.sum(dim=1)

prob_pos = torch.diag(exp_logits) / denom

loss = -torch.log(torch.clamp(prob_pos, min=1e-12)).mean()

return loss

# Reinit encoder for a clean run

enc = TinyEncoder(in_dim=2, out_dim=2, hidden=32)

opt = torch.optim.Adam(enc.parameters(), lr=1e-2)

losses = []

enc.train()

for step, (xa_b, xb_b) in enumerate(dl):

loss = batch_info_nce(enc, xa_b, xb_b, tau=0.1)

opt.zero_grad(set_to_none=True)

loss.backward()

opt.step()

losses.append(float(loss.item()))

if step % 10 == 0:

print(f"step {step:03d} loss={losses[-1]:.4f}")

plt.figure()

plt.plot(losses, marker="o")

plt.xlabel("step")

plt.ylabel("loss")

plt.title("Training loss on toy pairs")

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

step 000 loss=3.9659

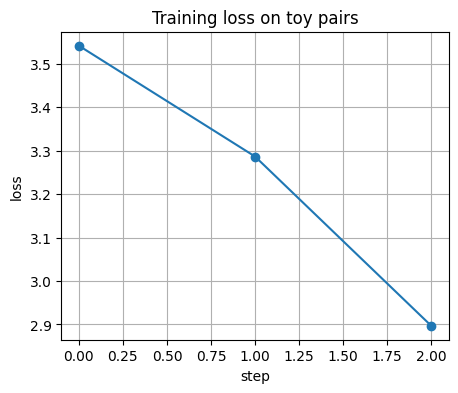

if torch is not None:

losses = []

enc.train()

for step, (xa_b, xb_b) in enumerate(dl):

loss = batch_info_nce(enc, xa_b, xb_b, tau=0.1)

opt.zero_grad(set_to_none=True)

loss.backward()

opt.step()

losses.append(float(loss.item()))

if step % 10 == 0:

print(f"step {step:03d} loss={losses[-1]:.4f}")

plt.figure()

plt.plot(losses, marker="o")

plt.xlabel("step")

plt.ylabel("loss")

plt.title("Training loss on toy pairs")

plt.show()

step 000 loss=3.5418

⏰ Exercise

Try a smaller learning rate 5e-3 and then a larger one 2e-2.

Does the loss curve become smoother or noisier?

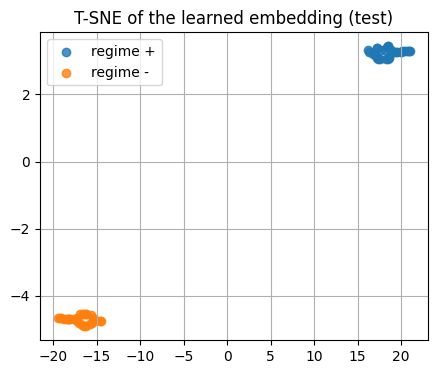

5.5 Visualize the learned embedding with T-SNE#

We embed the test set using the trained encoder.

Then we color by the hidden class to see clusters.

if torch is not None:

enc.eval()

with torch.no_grad():

z_test = enc(torch.from_numpy(X_test))

z_test_np = z_test.cpu().numpy()

show_shape("z_test_np", z_test_np)

# T-SNE on the learned embedding

tsne = TSNE(n_components=2, random_state=0, perplexity=20, init="random")

Z2 = tsne.fit_transform(z_test_np)

plt.figure()

plt.scatter(Z2[y_test==1,0], Z2[y_test==1,1], alpha=0.8, label="regime +")

plt.scatter(Z2[y_test==0,0], Z2[y_test==0,1], alpha=0.8, label="regime -")

plt.title("T-SNE of the learned embedding (test)")

plt.legend()

plt.show()

z_test_np.shape: (60, 2)

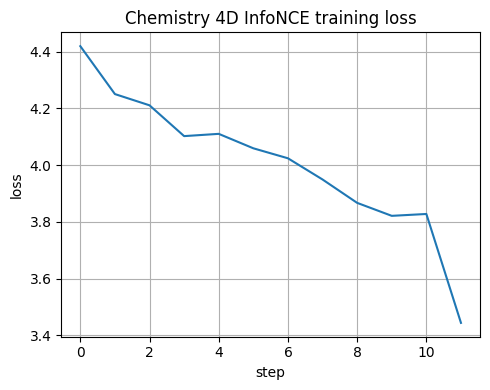

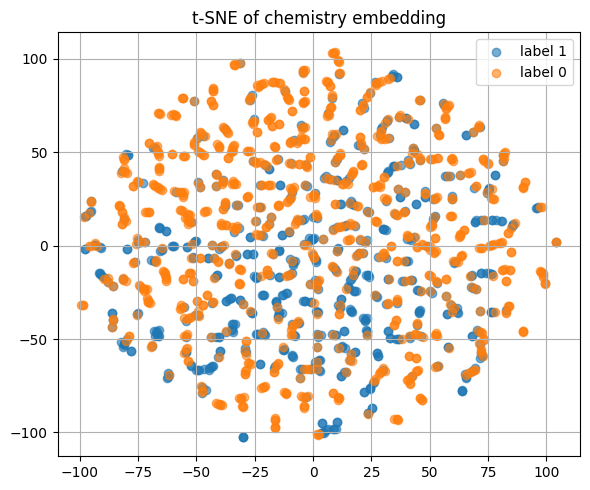

5.6 Tiny encoder trained on chemistry 4D conditions#

We now repeat the training on the chemistry dataset with 4 features.

We monitor the InfoNCE loss and later run a linear probe.

step 000 loss=4.4194

Z_chem.shape: (1500, 8)

Here is how encoded reaction conditions look like.

Z_chem_small[3:]

array([[ 0.2331, -0.0277, -0.5988, ..., -0.127 , 0.042 , -0.5624],

[-0.1021, 0.431 , -0.3986, ..., -0.2704, -0.0585, -0.7211],

[-0.1303, 0.4195, -0.287 , ..., -0.319 , -0.0759, -0.7696],

...,

[ 0.3989, -0.2529, -0.4264, ..., 0.119 , 0.065 , -0.4712],

[-0.1336, 0.4172, -0.2808, ..., -0.3187, -0.077 , -0.7732],

[-0.2229, 0.4902, -0.134 , ..., -0.327 , -0.1156, -0.7261]],

shape=(1497, 8), dtype=float32)

⏰ Exercise

Change out_dim from 3 to 2 and repeat the t-SNE plot.

See if the classes are more separated or less separated.

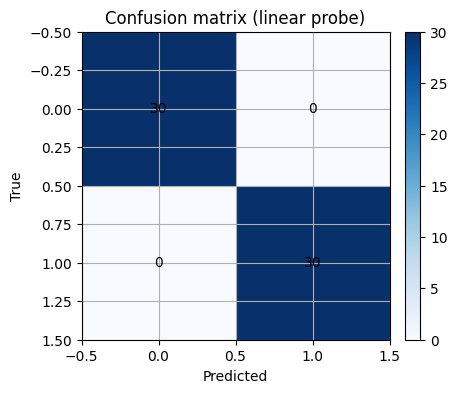

6. Linear evaluation and simple retrieval#

After contrastive pretraining, a common step is linear evaluation.

We freeze the encoder and train a simple classifier on top with a small labeled set.

6.1 Linear probe using logistic regression#

# If torch is missing, we will use raw features as a dummy "embedding"

if torch is None:

Z_train = X_train.copy()

Z_test = X_test.copy()

else:

enc.eval()

with torch.no_grad():

Z_train = enc(torch.from_numpy(X_train)).cpu().numpy()

Z_test = enc(torch.from_numpy(X_test)).cpu().numpy()

show_shape("Z_train", Z_train)

show_shape("Z_test", Z_test)

Z_train.shape: (180, 2)

Z_test.shape: (60, 2)

Z_train[:3]

array([[ 0.5109, 0.8596],

[-0.508 , -0.8614],

[-0.1346, -0.9909]], dtype=float32)

As you can see below, after converted to embedding, with simple machine learning model like LogisticRegression() you can easily classify what was quite challenging to do before.

sc = StandardScaler().fit(Z_train)

Ztr = sc.transform(Z_train)

Zte = sc.transform(Z_test)

clf = LogisticRegression(max_iter=500, random_state=0)

clf.fit(Ztr, y_train)

y_proba = clf.predict_proba(Zte)[:,1]

y_pred = (y_proba >= 0.5).astype(int)

print("Accuracy:", round(accuracy_score(y_test, y_pred), 3))

print("AUC:", round(roc_auc_score(y_test, y_proba), 3))

Accuracy: 1.0

AUC: 1.0

Exercise 7.1

Change the decision threshold from 0.5 to 0.3 and to 0.7.

Plot ROC and mark the two points.

Discuss how the tradeoff moves.

6.2 Retrieval with cosine similarity#

We take one query from the test set and retrieve the nearest neighbors in the embedding space.

This is useful to propose similar conditions or spectra for follow up experiments.

def topk_cosine(query, items, k=5):

q = query.reshape(1, -1)

items_n = normalize(items, norm="l2", axis=1)

q_n = normalize(q, norm="l2", axis=1)

sims = (items_n @ q_n.T).ravel()

idx = np.argsort(-sims)[:k]

return idx, sims[idx]

q_idx = 2

q = Z_test[q_idx]

idx, sims = topk_cosine(q, Z_test, k=6) # include itself

print("Query is index", q_idx, "with class", y_test[q_idx])

print("Top indices:", idx)

print("Top sims :", np.round(sims, 3))

Query is index 2 with class 1

Top indices: [ 2 42 17 47 58 14]

Top sims : [1. 1. 1. 0.999 0.998 0.998]

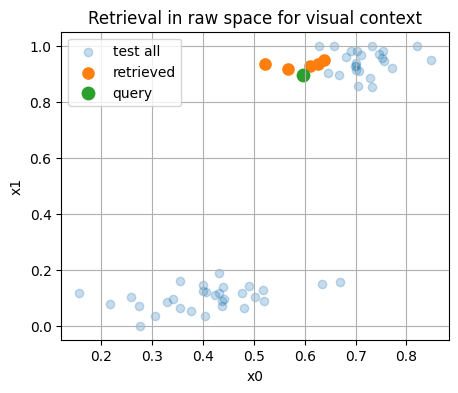

# Visualize query and neighbors in raw 2D space for context

plt.figure()

plt.scatter(X_test[:,0], X_test[:,1], alpha=0.25, label="test all")

plt.scatter(X_test[idx,0], X_test[idx,1], s=65, label="retrieved")

plt.scatter([X_test[q_idx,0]],[X_test[q_idx,1]], s=80, label="query")

plt.xlabel("x0"); plt.ylabel("x1")

plt.title("Retrieval in raw space for visual context")

plt.legend()

plt.show()

⏰ Exercise

Replace q_idx = 2 with another index.

Check if the nearest neighbors share the same label more often than random picks.

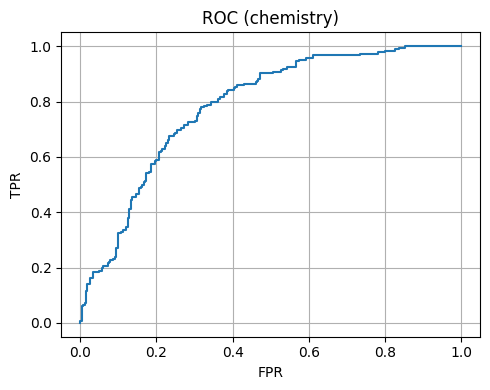

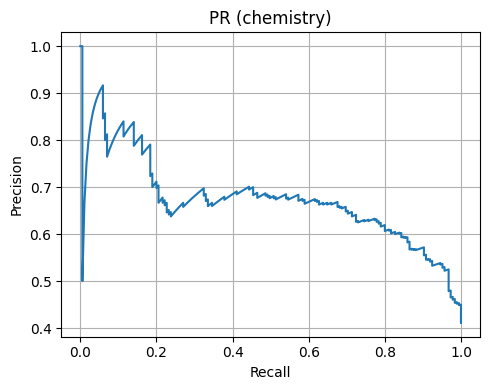

6.3 Linear probe and curves on chemistry 4D#

We embed the chemistry dataset if an encoder was trained, then fit a probe.

We plot ROC and Precision-Recall.

Chemistry 4D Accuracy: 0.696

Chemistry 4D AUC: 0.784

7. Mini case studies#

Contrastive learning depends on good view design.

In chemistry, the view should preserve the identity of the sample while adding realistic variation.

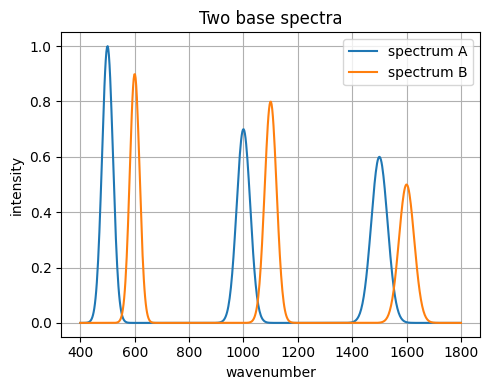

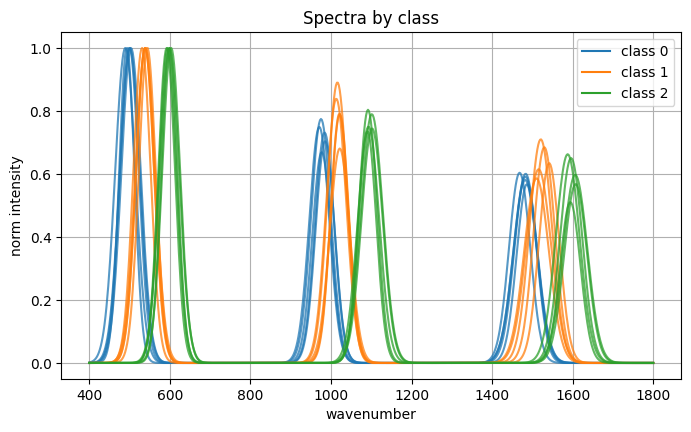

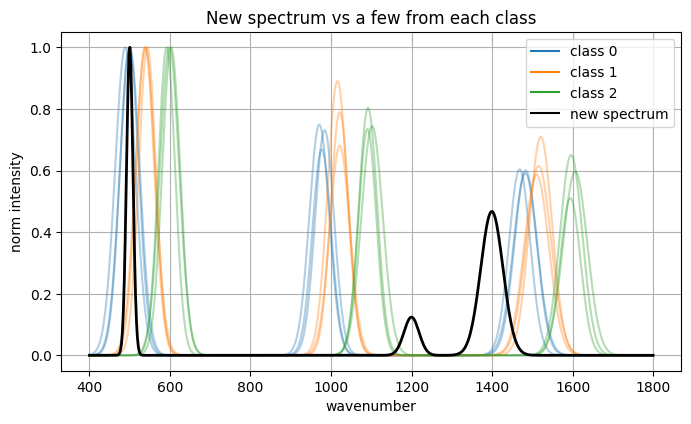

7.1 Spectra toy example: IR-like peaks with noise#

We synthesize spectra as sums of Gaussians.

Two views of the same sample will get small baseline shifts and noise.

# Build synthetic 1D spectra

def gaussian(x, mu, sig, amp):

return amp * np.exp(-0.5 * ((x-mu)/sig)**2)

def make_spectrum(x, peaks):

y = np.zeros_like(x)

for (mu, sig, amp) in peaks:

y += gaussian(x, mu, sig, amp)

return y

x_grid = np.linspace(400, 1800, 600) # wavenumbers

peaks_A = [(500, 20, 1.0), (1000, 25, 0.7), (1500, 30, 0.6)]

peaks_B = [(600, 18, 0.9), (1100, 22, 0.8), (1600, 28, 0.5)]

spec_A = make_spectrum(x_grid, peaks_A)

spec_B = make_spectrum(x_grid, peaks_B)

plt.figure()

plt.plot(x_grid, spec_A, label="spectrum A")

plt.plot(x_grid, spec_B, label="spectrum B")

plt.xlabel("wavenumber")

plt.ylabel("intensity")

plt.title("Two base spectra")

plt.legend()

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

# Augmentations for spectra

def add_baseline(y, slope_std=0.0005):

slope = rng.normal(0.0, slope_std)

baseline = slope * (np.arange(len(y)) - len(y)/2.0)

return y + baseline

def add_noise(y, std=0.02):

return y + rng.normal(0.0, std, size=len(y))

def scale_intensity(y, s_std=0.05):

s = 1.0 + rng.normal(0.0, s_std)

return y * s

def normalize_minmax(y):

ymin, ymax = y.min(), y.max()

if ymax - ymin < 1e-9:

return y.copy()

return (y - ymin) / (ymax - ymin)

def view_spectrum(y):

z = add_baseline(y, 0.0004)

z = add_noise(z, 0.02)

z = scale_intensity(z, 0.03)

return normalize_minmax(z)

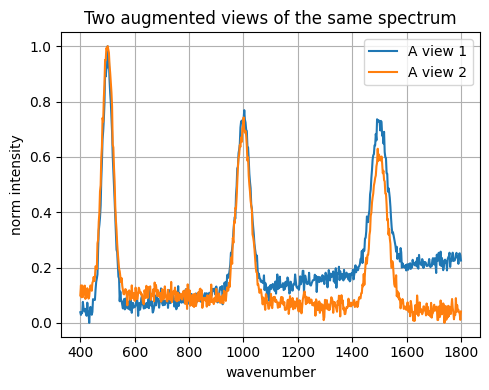

# Make two views for A

vA1 = view_spectrum(spec_A)

vA2 = view_spectrum(spec_A)

plt.figure()

plt.plot(x_grid, vA1, label="A view 1")

plt.plot(x_grid, vA2, label="A view 2")

plt.xlabel("wavenumber"); plt.ylabel("norm intensity")

plt.title("Two augmented views of the same spectrum")

plt.legend()

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

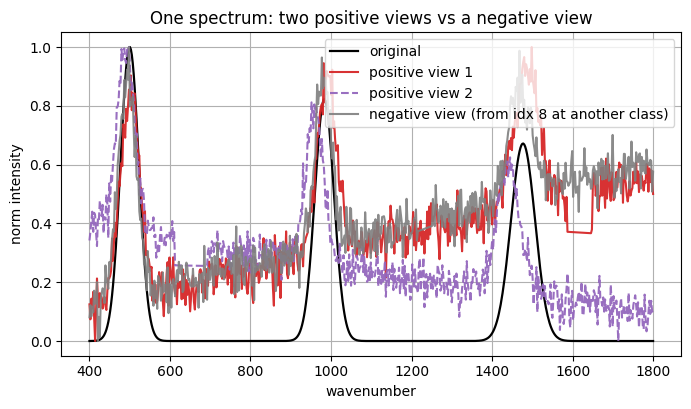

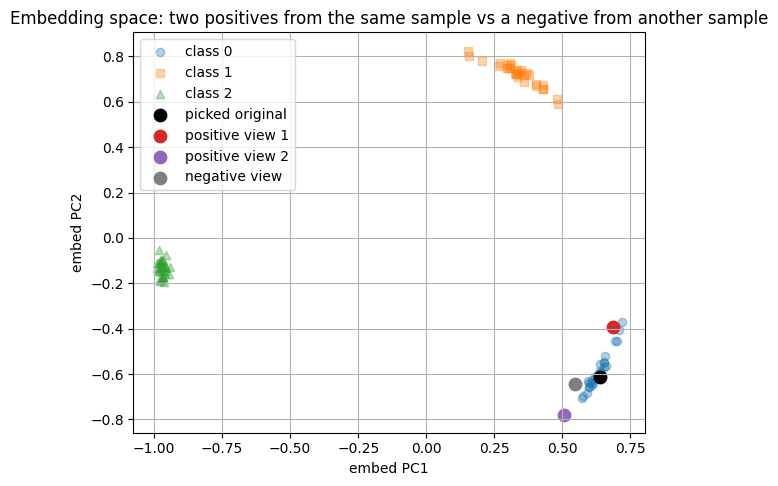

Below, you will see how constrative learning helps convert the spectrum data into embeddings with careful data augmentation and these embeddings are used to downstream tasks like classification.

Dataset:

spectra array shape: (90, 600) dtype: float32

labels array shape: (90,) classes: [0, 1, 2]

Picked spectrum index: 7 class: 0

original shape: (600,)

pos1 shape: (600,)

pos2 shape: (600,)

neg view source idx: 8 class: 0

Encoded representations (first 6 of 16):

enc(original): [-0.0662 0.0072 0.4778 0.1843 -0.1229 -0.0433]

enc(pos1): [-0.1873 0.1057 0.3848 0.3222 -0.0155 -0.1182]

enc(pos2): [ 0.0203 -0.0228 0.4331 0.2664 -0.0857 -0.045 ]

enc(neg): [-0.07 0.001 0.3886 0.309 -0.037 -0.0928]

Classifier on embeddings:

train size: 36 test size: 54

test accuracy: 1.0

C:\Users\52377\AppData\Local\Programs\Python\Python313\Lib\site-packages\sklearn\linear_model\_logistic.py:1281: FutureWarning: 'multi_class' was deprecated in version 1.5 and will be removed in 1.7. Use OneVsRestClassifier(LogisticRegression(..)) instead. Leave it to its default value to avoid this warning.

warnings.warn(

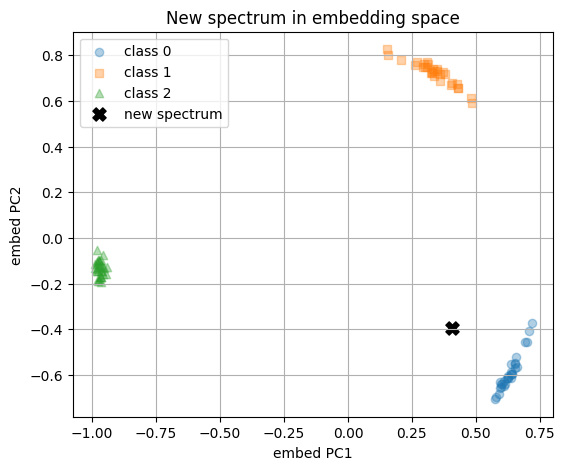

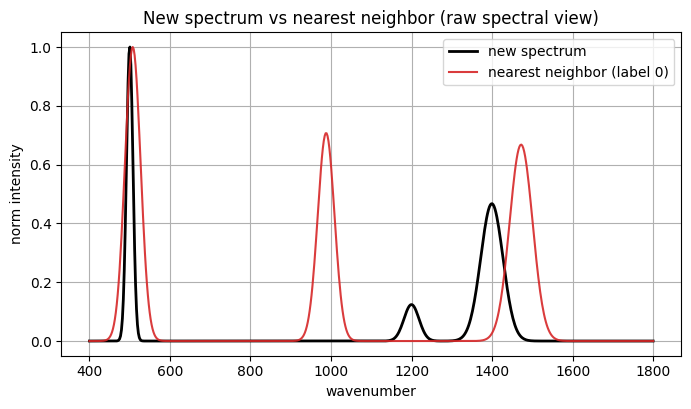

Now we have a new spectrum and we turn it to embedding with the encoder and feed the embedding to trained model to give prediction.

Encoded new spectrum (first 8 dims): [-0.2255 -0.2099 0.3495 0.0591 0.0072 -0.165 0.0601 -0.3685]

Predicted class: 0

Class probabilities: [0.857, 0.088, 0.055]

Nearest neighbor index in existing set: 9

Nearest neighbor label: 0

Cosine similarity in embedding space: 0.8782

8. Glossary#

- Contrastive learning#

A method that trains an embedding so that two views of the same item are close and different items are far.

- Positive pair#

Two augmented views of the same sample. They should remain close in the embedding.

- Negative pair#

Two views from different samples. They should be far in the embedding.

- Cosine similarity#

The dot product of normalized vectors. It measures alignment of directions.

- Temperature#

A positive scalar in softmax that controls smoothness. Smaller values make distributions peakier.

- InfoNCE loss#

A loss that maximizes agreement of the correct pair while contrasting against other items in the batch.

- Linear probe#

A simple classifier trained on frozen embeddings to check if information is linearly recoverable.

- Augmentation#

A transformation that preserves identity while adding variation such as noise or small jitters.

- View#

The result of applying an augmentation to a sample. Two views of the same sample form a positive pair.

- Retrieval#

Given a query in embedding space, return nearest neighbors by a similarity such as cosine.