Lecture 6 - Cross-Validation#

Learning goals#

1. Dataset and setup#

Why this dataset?

We will reuse the same table from Lecture 5. It includes SMILES plus targets such as Melting Point and Toxicity. We compute four lightweight descriptors that we already trust: MolWt, LogP, TPSA, NumRings. They are fast to compute, easy to interpret, and good enough to demonstrate model selection and cross‑validation.

1.1 Imports and environment#

1.2 Load data and build descriptors#

Data source

We will use this C-H oxidation dataset we saw before:

https://raw.githubusercontent.com/zzhenglab/ai4chem/main/book/_data/C_H_oxidation_dataset.csv

url = "https://raw.githubusercontent.com/zzhenglab/ai4chem/main/book/_data/C_H_oxidation_dataset.csv"

df_raw = pd.read_csv(url)

def calc_descriptors_row(smiles):

m = Chem.MolFromSmiles(smiles)

if m is None:

return pd.Series({"MolWt": np.nan, "LogP": np.nan, "TPSA": np.nan, "NumRings": np.nan})

return pd.Series({

"MolWt": Descriptors.MolWt(m),

"LogP": Crippen.MolLogP(m),

"TPSA": rdMolDescriptors.CalcTPSA(m),

"NumRings": rdMolDescriptors.CalcNumRings(m),

})

desc_df = df_raw["SMILES"].apply(calc_descriptors_row)

df_reg_mp = pd.concat([df_raw, desc_df], axis=1)

df_reg_mp.head()

| Compound Name | CAS | SMILES | Solubility_mol_per_L | pKa | Toxicity | Melting Point | Reactivity | Oxidation Site | MolWt | LogP | TPSA | NumRings | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 3,4-dihydro-1H-isochromene | 493-05-0 | c1ccc2c(c1)CCOC2 | 0.103906 | 5.80 | non_toxic | 65.8 | 1 | 8,10 | 134.178 | 1.7593 | 9.23 | 2.0 |

| 1 | 9H-fluorene | 86-73-7 | c1ccc2c(c1)Cc1ccccc1-2 | 0.010460 | 5.82 | toxic | 90.0 | 1 | 7 | 166.223 | 3.2578 | 0.00 | 3.0 |

| 2 | 1,2,3,4-tetrahydronaphthalene | 119-64-2 | c1ccc2c(c1)CCCC2 | 0.020589 | 5.74 | toxic | 69.4 | 1 | 7,10 | 132.206 | 2.5654 | 0.00 | 2.0 |

| 3 | ethylbenzene | 100-41-4 | CCc1ccccc1 | 0.048107 | 5.87 | non_toxic | 65.0 | 1 | 1,2 | 106.168 | 2.2490 | 0.00 | 1.0 |

| 4 | cyclohexene | 110-83-8 | C1=CCCCC1 | 0.060688 | 5.66 | non_toxic | 96.4 | 1 | 3,6 | 82.146 | 2.1166 | 0.00 | 1.0 |

What these features mean

MolWt: molecular weight (sum of atomic masses).

LogP: hydrophobicity descriptor (octanol/water partition).

TPSA: topological polar surface area.

NumRings: ring count.

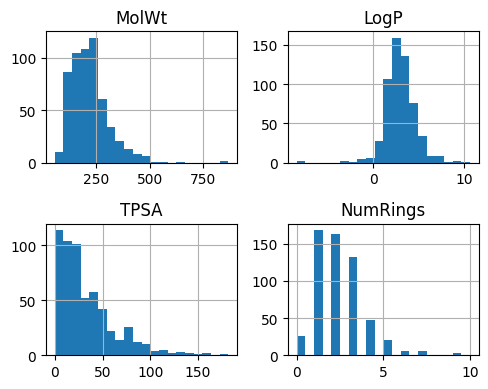

2. Quick Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA)#

2.1 Descriptor histograms#

Goal

Check scale, spread, and any extreme values. If a feature is highly skewed, consider transforms or standardization before training.

features = ["MolWt", "LogP", "TPSA", "NumRings"]

ax = df_reg_mp[features].hist(bins=20, figsize=(5,4))

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

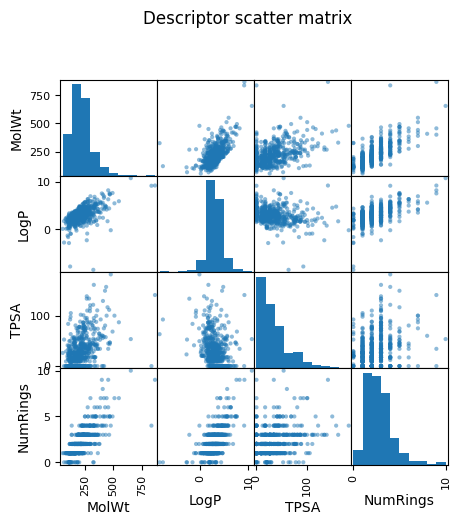

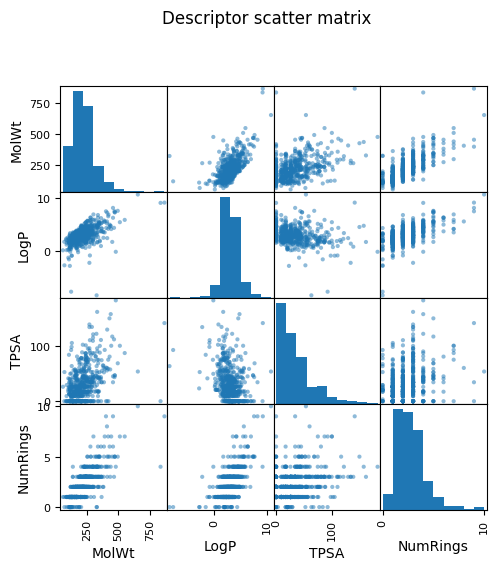

2.2 Pairwise relationships#

pd.plotting.scatter_matrix(df_reg_mp[features], figsize=(5,5))

plt.suptitle("Descriptor scatter matrix", y=1.02)

plt.show()

As you see above, a pairwise plot (also called a scatterplot matrix) shows relationships between every possible pair of features. For example, if you have four descriptors — MolWt, LogP, TPSA, and NumRings — the matrix will draw 12 scatterplots pairs (diagonal being their own distribution).

Why we look at pairwise plots?

Spot correlations: If two descriptors are strongly correlated (for example, heavier molecules often have higher logP), you can see it visually. Highly correlated pairs may be redundant.

Detect outliers: Points that are far away from the general cloud of data stand out.

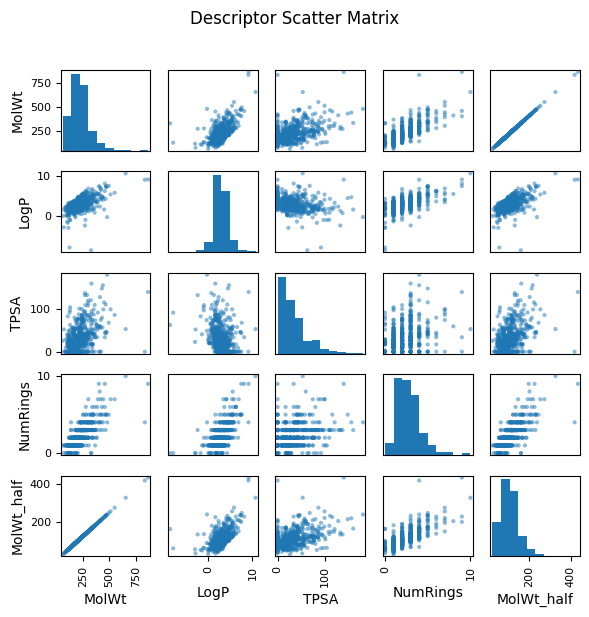

2.3 Redundancy demo and correlation#

To illustrate what redundancy looks like, in the following example, we added a synthetic feature called MolWt_half, created simply by multiplying molecular weight by 0.5. In the scatter matrix, MolWt_half and MolW form a perfect straight-line relationship, highlighting redundancy.

In real-world datasets, you might encounter similar situations where two measured properties track one another closely because they arise from the same underlying physical or chemical trend. In such cases, redundancy reduces the effective dimensionality of the dataset.

This visual impression can be confirmed by calculating the correlation coefficient numerically. A correlation near 1.0 (or –1.0) indicates strong redundancy, just like we see between MolWt and MolWt_half.

# Add demo redundant feature

df_reg_mp["MolWt_half"] = df_reg_mp["MolWt"] * 0.5

# Choose features to visualize

features = ["MolWt", "LogP", "TPSA", "NumRings", "MolWt_half"]

# Numerical correlation matrix

print("\nCorrelation Matrix (rounded to 3 decimals):")

corr_matrix = df_reg_mp[features].corr().round(3)

print(corr_matrix)

# Scatter matrix

pd.plotting.scatter_matrix(df_reg_mp[features], figsize=(6,6), diagonal="hist")

plt.suptitle("Descriptor Scatter Matrix", y=1.02)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

Correlation Matrix (rounded to 3 decimals):

MolWt LogP TPSA NumRings MolWt_half

MolWt 1.000 0.595 0.447 0.759 1.000

LogP 0.595 1.000 -0.268 0.605 0.595

TPSA 0.447 -0.268 1.000 0.294 0.447

NumRings 0.759 0.605 0.294 1.000 0.759

MolWt_half 1.000 0.595 0.447 0.759 1.000

3. Introduction to hyperparameters#

Lasso refresher

Lasso solves a linear regression with an L1 penalty. The loss (on a dataset of size n) is

[

\frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^n (y_i - \hat{y}_i)^2 + \alpha \sum_j |w_j|

]

When (\alpha) is larger, more coefficients go to zero.

3.1 Single split evaluation#

When we fit a model, we often think about weights (w) that are learned from the data. But some knobs are not learned automatically — they are chosen by us. These are called hyperparameters. One of the most important hyperparameters in Lasso is alpha. As you may recall from last lecture, it controls the strength of the L1 penalty.

# Define X (features) and y (target)

X = df_reg_mp[["MolWt", "LogP", "TPSA", "NumRings"]]

y = df_reg_mp["Melting Point"]

# Split into train (80%) and test (20%) sets

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(

X, y, test_size=0.2, random_state=1

)

# Define models in a dictionary

models = {

"Linear Regression": LinearRegression(),

"Lasso (alpha=0.1)": Lasso(alpha=0.1, max_iter=500),

"Lasso (alpha=1)": Lasso(alpha=1, max_iter=500),

"Lasso (alpha=10)": Lasso(alpha=10, max_iter=500),

"Lasso (alpha=100)": Lasso(alpha=100, max_iter=500),

"Lasso (alpha=500)": Lasso(alpha=500, max_iter=500)

}

# Collect results

results = []

for name, model in models.items():

model.fit(X_train, y_train)

y_pred = model.predict(X_test)

mse_val = mean_squared_error(y_test, y_pred)

mae_val = mean_absolute_error(y_test, y_pred)

r2_val = r2_score(y_test, y_pred)

results.append([name, mse_val, mae_val, r2_val])

# Put results in a nice DataFrame

df_results = pd.DataFrame(results, columns=["Model", "MSE", "MAE", "R2"])

df_results

| Model | MSE | MAE | R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Linear Regression | 398.206541 | 16.006228 | 0.816101 |

| 1 | Lasso (alpha=0.1) | 396.546775 | 15.975604 | 0.816868 |

| 2 | Lasso (alpha=1) | 389.603474 | 15.816549 | 0.820074 |

| 3 | Lasso (alpha=10) | 390.347484 | 15.855184 | 0.819731 |

| 4 | Lasso (alpha=100) | 399.273984 | 16.080242 | 0.815608 |

| 5 | Lasso (alpha=500) | 423.683879 | 16.757040 | 0.804335 |

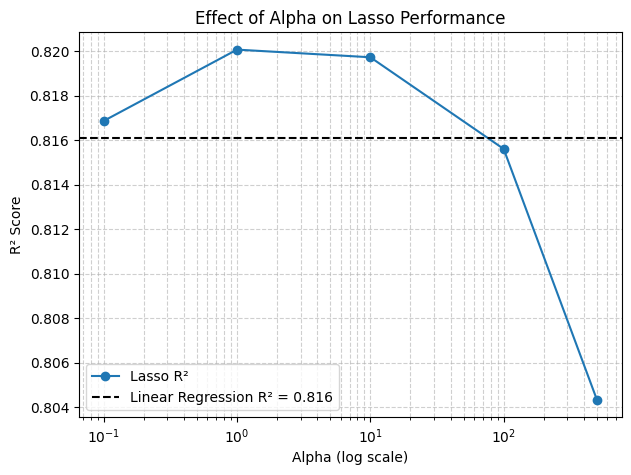

3.2 Effect of alpha (plot)#

# Extract results for plotting

lasso_results = df_results[df_results["Model"].str.contains("Lasso")]

alphas = [0.1, 1, 10, 100, 500]

r2_scores = lasso_results["R2"].values

# Linear Regression baseline

linear_r2 = df_results.loc[df_results["Model"] == "Linear Regression", "R2"].values[0]

# Plot R² vs alpha

plt.figure(figsize=(7,5))

plt.semilogx(alphas, r2_scores, marker="o", label="Lasso R²")

plt.axhline(linear_r2, color="k", linestyle="--", label=f"Linear Regression R² = {linear_r2:.3f}")

plt.xlabel("Alpha (log scale)")

plt.ylabel("R² Score")

plt.title("Effect of Alpha on Lasso Performance")

plt.legend()

plt.grid(True, which="both", linestyle="--", alpha=0.6)

plt.show()

4. Cross validation#

So far we evaluated models with a single 80/20 split, which can give performance estimates that depend strongly on the random split. To obtain a more reliable measure, we can use 4-fold cross validation*. This way, the dataset is split into 4 equal parts, and each part is used once as the test set while the other 3 parts are used for training. The metrics are then averaged across the 4 folds.

Why CV?

A single split can overestimate or underestimate performance. K-fold CV repeats the split several times and averages the metric, giving a more stable estimate.

alphas = [0.1, 1, 10, 100]

kf = KFold(n_splits=4, shuffle=True, random_state=1)

for a in alphas:

model = Lasso(alpha=a, max_iter=500)

scores = cross_val_score(model, X, y, cv=kf, scoring="r2")

print(f"alpha={a}, Scores on each fold: {scores} \n mean R²={scores.mean():.5f} \n")

alpha=0.1, Scores on each fold: [0.80086458 0.8800675 0.85024608 0.81400961]

mean R²=0.83630

alpha=1, Scores on each fold: [0.8012391 0.88025613 0.85027326 0.81361778]

mean R²=0.83635

alpha=10, Scores on each fold: [0.80123962 0.88012751 0.85111665 0.81276335]

mean R²=0.83631

alpha=100, Scores on each fold: [0.79943866 0.87767314 0.85590684 0.80952064]

mean R²=0.83563

Exercise 4.1

Change the alphas to [0.05, 0.5, 1, 2, 5, 15, 30, 100].

Use 5-fold CV and the neg_mean_squared_error scorer.

Print the per-fold values and the mean MSE.

5. Model selection, evaluation and prediction#

Plan

Pick an alpha using CV, fit on train, evaluate on held‑out test, then apply to new molecules.

from sklearn.model_selection import KFold, cross_validate

# Define X and y again

X = df_reg_mp[["MolWt", "LogP", "TPSA", "NumRings"]]

y = df_reg_mp["Melting Point"]

# Train/test split

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y, test_size=0.2, random_state=1)

# Use 4-fold cross validation

kf = KFold(n_splits=4, shuffle=True, random_state=1)

# Same models as before

models = {

"Linear Regression": LinearRegression(),

"Lasso (alpha=0.1)": Lasso(alpha=0.1, max_iter=500),

"Lasso (alpha=1)": Lasso(alpha=1, max_iter=500),

"Lasso (alpha=10)": Lasso(alpha=10, max_iter=500),

"Lasso (alpha=30)": Lasso(alpha=30, max_iter=500),

"Lasso (alpha=100)": Lasso(alpha=100, max_iter=500)

}

results_cv = []

for name, model in models.items():

cv_results = cross_validate(

model, X_train, y_train,

cv=kf,

scoring=["r2", "neg_mean_squared_error", "neg_mean_absolute_error"],

return_train_score=False

)

# Compute mean and std across folds

mean_r2 = cv_results["test_r2"].mean()

mean_mse = -cv_results["test_neg_mean_squared_error"].mean()

mean_mae = -cv_results["test_neg_mean_absolute_error"].mean()

results_cv.append([name, mean_mse, mean_mae, mean_r2])

# Put results in a DataFrame

df_results_cv = pd.DataFrame(results_cv, columns=["Model", "MSE", "MAE", "R2"])

print(df_results_cv)

Model MSE MAE R2

0 Linear Regression 410.132745 15.969645 0.832197

1 Lasso (alpha=0.1) 409.638038 15.958751 0.832326

2 Lasso (alpha=1) 408.902710 15.918428 0.832658

3 Lasso (alpha=10) 408.189050 15.900646 0.833132

4 Lasso (alpha=30) 408.099029 15.906188 0.833208

5 Lasso (alpha=100) 408.969334 15.961744 0.832932

Based on above table, you know alpha = 30 works best for this case. Let’s assign this value to build a model, fit with data and evaluate the outcome, which can be completed within three lines.

alpha_optimized_model = Lasso(alpha=30, max_iter=500)

fitted_lasso = alpha_optimized_model.fit(X_train, y_train)

print(f"Test R² = {r2_score(y_test, fitted_lasso.predict(X_test)):.3f} when we use alpha = 30")

Test R² = 0.818 when we use alpha = 30

R² = 0.820 tells us how good the fitting is. Note this R² is calculated based on the final hold-out test set, so it will be different from the R² one we see during the CV (0.833). The fact that they are very similar to each other is a good sign because this model has never seen any datapoint from X_test before but can still do a good prediction.

Now we can use this function to give prediction for points that are neither in train and test data set. For example, we can predict two molecules’s melting point by listing their descriptors.

Predict new points

We can predict from raw descriptors, or compute descriptors from SMILES first (see example below).

fitted_lasso.predict(pd.DataFrame([[100, 1.5, 10, 2],

[150, 2.0, 20, 3]],

columns=["MolWt", "LogP", "TPSA", "NumRings"]))

array([70.44917852, 95.30123863])

smiles_list = ["C1CCCC(C)C1", "CCCO"]

# Explicitly call your function for each SMILES

desc_rows = [calc_descriptors_row(s) for s in smiles_list]

# Build DataFrame

new_desc = pd.DataFrame(desc_rows)

new_desc

| MolWt | LogP | TPSA | NumRings | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 98.189 | 2.5866 | 0.00 | 1.0 |

| 1 | 60.096 | 0.3887 | 20.23 | 0.0 |

# Predict

two_new_preds = fitted_lasso.predict(new_desc)

# Show results

results = pd.DataFrame({"SMILES": smiles_list, "Prediction": two_new_preds})

print(results)

SMILES Prediction

0 C1CCCC(C)C1 69.345037

1 CCCO 51.000708

If your combine all above together, the workflow will look like:

Define features and target (

MolWt,LogP,TPSA,NumRings→Melting Point).Split data: 80% train, 20% test.

Model selection

Last lecture: fit on train directly if no hyperparameter tuning needed.

Lasso Regression (this lecture): use 4-fold cross-validation on train to pick best alpha, then refit on full train.

Evaluate chosen model on test set for generalization.

Apply final model to new molecules for prediction.

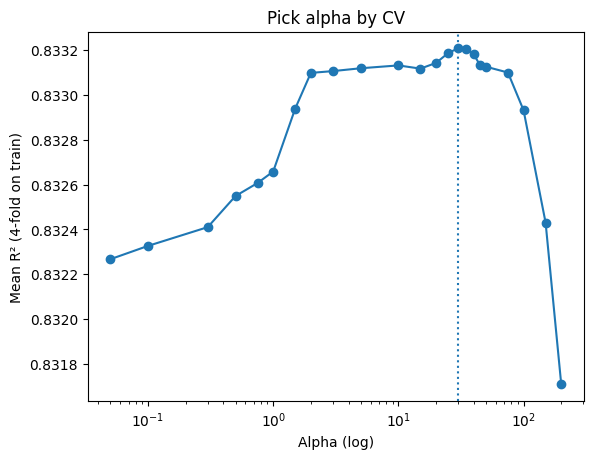

6. End‑to‑end workflow and grid search#

Two ways to choose alpha

Manual loop over a grid and pick the best mean CV score.

GridSearchCVto automate the loop, scoring, and refit.

# 1) Features and target

X = df_reg_mp[["MolWt", "LogP", "TPSA", "NumRings"]]

y = df_reg_mp["Melting Point"]

# 2) Train/test split

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y, test_size=0.2, random_state=1)

# 3 Choose alpha using 4-fold CV on TRAIN ONLY

alphas = [0.05, 0.1, 0.3, 0.5, 0.75, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 5, 10,

15, 20, 25, 30, 35, 40, 45, 50, 75, 100, 150, 200]

kf = KFold(n_splits=4, shuffle=True, random_state=1)

mean_r2 = []

for a in alphas:

model = Lasso(alpha=a, max_iter=500)

r2_vals = cross_val_score(model, X_train, y_train, cv=kf, scoring="r2")

mean_r2.append(r2_vals.mean())

best_alpha = alphas[int(np.argmax(mean_r2))]

print(f"Best alpha: {best_alpha} (mean R² = {max(mean_r2):.3f})")

# 4) Fit with best alpha on TRAIN, evaluate on TEST

final_lasso = Lasso(alpha=best_alpha, max_iter=500).fit(X_train, y_train)

# 5) Evaluate

y_pred = final_lasso.predict(X_test)

print(f"Test R² = {r2_score(y_test, y_pred):.3f}")

# Optional: compare to plain Linear Regression

lr = LinearRegression().fit(X_train, y_train)

print(f"Linear Regression Test R² = {r2_score(y_test, lr.predict(X_test)):.3f}")

# Quick plot of the selection

plt.semilogx(alphas, mean_r2, marker="o")

plt.axvline(best_alpha, linestyle=":")

plt.xlabel("Alpha (log)"); plt.ylabel("Mean R² (4-fold on train)"); plt.title("Pick alpha by CV")

plt.show()

Best alpha: 30 (mean R² = 0.833)

Test R² = 0.818

Linear Regression Test R² = 0.816

The block above actually shows a manual grid search: you loop through candidate alphas, run cross-validation, collect mean R² scores, and then pick the best alpha before refitting on the training set.

Now, the second block below shows the same idea implemented with GridSearchCV: it automates the loop, scoring, and best-alpha selection. With refit=True, the best model is automatically retrained on the full training data, so you can directly use grid.best_estimator_ for evaluation.

# 1) Data

X = df_reg_mp[["MolWt", "LogP", "TPSA", "NumRings"]]

y = df_reg_mp["Melting Point"]

# 2) Train/test split

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y, test_size=0.2, random_state=1)

# 3a) Define model and CV

lasso = Lasso(max_iter=500)

param_grid = {"alpha": [0.05, 0.1, 0.3, 0.5, 0.75, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 5,

10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 35, 40, 45, 50, 75,

100, 150, 200]}

cv = KFold(n_splits=4, shuffle=True, random_state=1)

# 3b) Grid search on TRAIN

grid = GridSearchCV(lasso, param_grid, cv=cv, scoring="r2", refit=True)

grid.fit(X_train, y_train)

print(f"Best alpha: {grid.best_params_['alpha']} (mean R^2 = {grid.best_score_:.3f})")

# 4) Best model (already fitted)

final_lasso = grid.best_estimator_

# 5) Evaluate on TEST

y_pred = final_lasso.predict(X_test)

print(f"Test R^2 = {r2_score(y_test, y_pred):.3f}")

Best alpha: 30 (mean R^2 = 0.833)

Test R^2 = 0.818

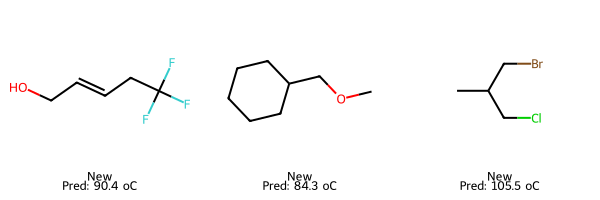

# 5) Predict on new molecules

smiles_three_new = ["C(F)(F)(F)CC=CCO", "C1CCCC(COC)C1", "CC(CBr)CCl"]

# Compute descriptors for each SMILES

smiles_three_new_desc = pd.DataFrame([calc_descriptors_row(s) for s in smiles_three_new])

# Predict for valid rows

smiles_three_new_preds = final_lasso.predict(smiles_three_new_desc)

# Show results

results = pd.DataFrame({"SMILES": np.array(smiles_three_new), "Prediction": smiles_three_new_preds})

print(results.to_string(index=False))

SMILES Prediction

C(F)(F)(F)CC=CCO 90.429280

C1CCCC(COC)C1 84.337454

CC(CBr)CCl 105.456027

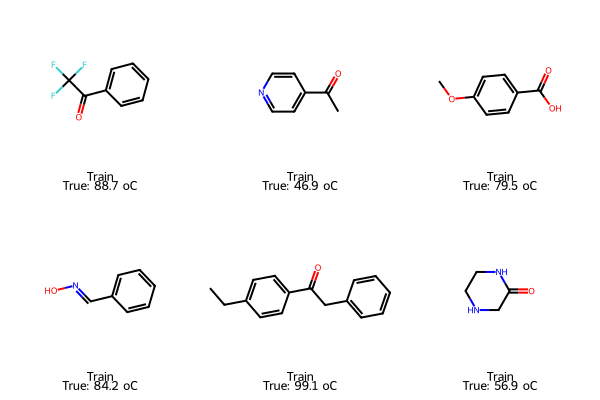

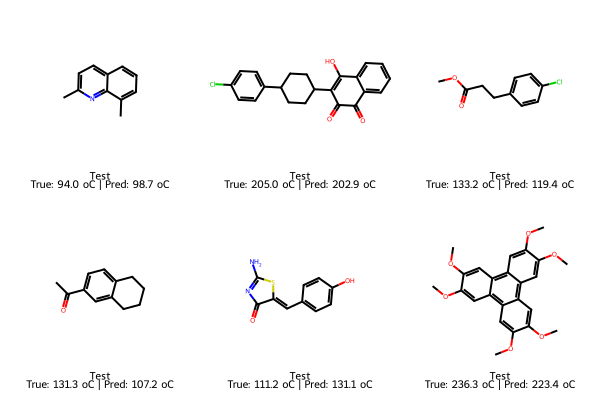

We can also plot some representative molecules in train and test set, as well as some new molecules we want to predict outside the exisiting dataset.

# Pick samples

train_idx = X_train.sample(6, random_state=101).index

test_idx = X_test.sample(6, random_state=202).index

# Train: true only

train_smiles = df_reg_mp.loc[train_idx, "SMILES"].tolist()

train_true = y_train.loc[train_idx].tolist()

img_train = Draw.MolsToGridImage(

[Chem.MolFromSmiles(s) for s in train_smiles],

molsPerRow=3, subImgSize=(200,200),

legends=[f"Train\nTrue: {t:.1f} oC" for t in train_true]

)

# Test: true and predicted

test_smiles = df_reg_mp.loc[test_idx, "SMILES"].tolist()

test_true = y_test.loc[test_idx].tolist()

test_pred = final_lasso.predict(X_test.loc[test_idx])

img_test = Draw.MolsToGridImage(

[Chem.MolFromSmiles(s) for s in test_smiles],

molsPerRow=3, subImgSize=(200,200),

legends=[f"Test\nTrue: {t:.1f} oC | Pred: {p:.1f} oC"

for t,p in zip(test_true, test_pred)]

)

# New: predicted only

smiles_new = ["C(F)(F)(F)CC=CCO", "C1CCCC(COC)C1", "CC(CBr)CCl"]

X_new = pd.DataFrame([calc_descriptors_row(s) for s in smiles_new])[final_lasso.feature_names_in_]

pred_new = final_lasso.predict(X_new)

img_new = Draw.MolsToGridImage(

[Chem.MolFromSmiles(s) for s in smiles_new],

molsPerRow=3, subImgSize=(200,200),

legends=[f"New\nPred: {p:.1f} oC" for p in pred_new]

)

display(img_train); display(img_test); display(img_new)

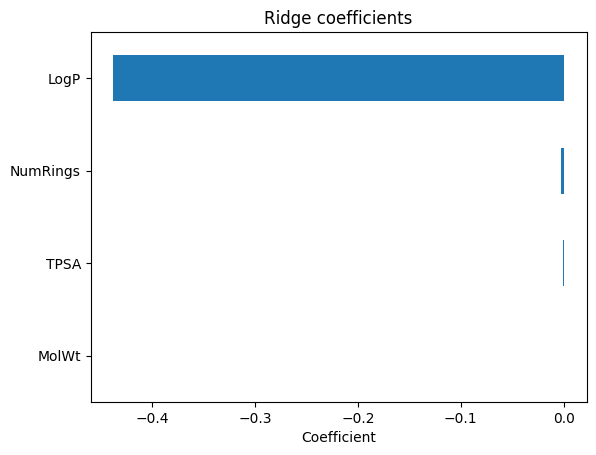

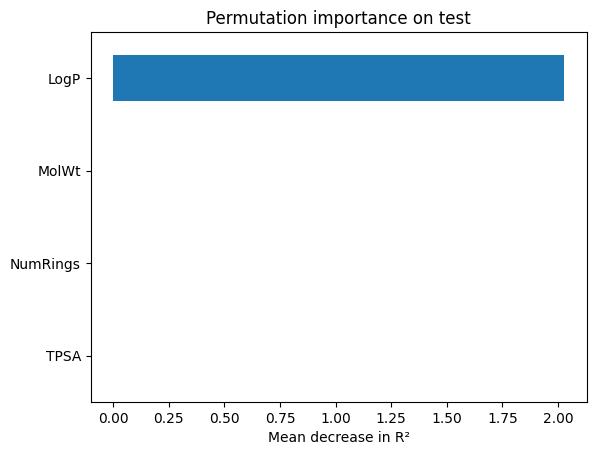

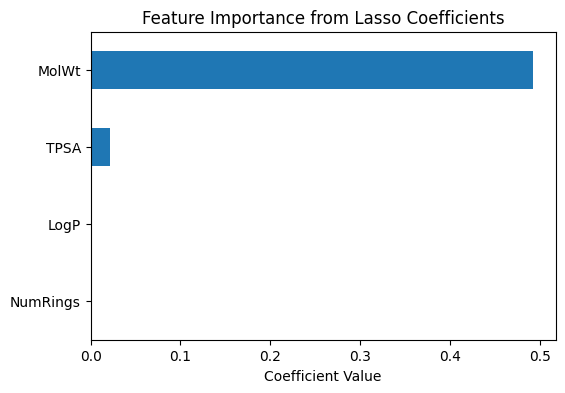

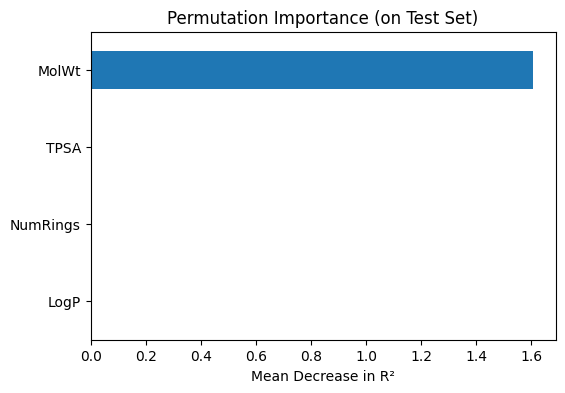

7. Explaining the model with feature importance#

Two views

Coefficients: direction and weight (Lasso shrinks some to zero).

Permutation importance: how much test R² drops when a feature is shuffled.

# --- Coefficient-based importance (Lasso) ---

coef_importance = pd.Series(

final_lasso.coef_,

index=final_lasso.feature_names_in_

).sort_values(key=abs, ascending=False)

print("Lasso coefficients (feature importance):")

print(coef_importance)

# Plot coefficients

coef_importance.plot(kind="barh", figsize=(6,4))

plt.title("Feature Importance from Lasso Coefficients")

plt.xlabel("Coefficient Value")

plt.gca().invert_yaxis()

plt.show()

# --- Permutation importance (model agnostic) ---

perm_importance = permutation_importance(

final_lasso, X_test, y_test,

scoring="r2", n_repeats=20, random_state=1

)

perm_series = pd.Series(

perm_importance.importances_mean,

index=final_lasso.feature_names_in_

).sort_values(ascending=True)

print("\nPermutation importance (mean decrease in R²):")

print(perm_series)

# Plot permutation importance

perm_series.plot(kind="barh", figsize=(6,4))

plt.title("Permutation Importance (on Test Set)")

plt.xlabel("Mean Decrease in R²")

plt.show()

Lasso coefficients (feature importance):

MolWt 0.492808

TPSA 0.021167

LogP -0.000000

NumRings -0.000000

dtype: float64

Permutation importance (mean decrease in R²):

LogP 0.000000

NumRings 0.000000

TPSA 0.002218

MolWt 1.607811

dtype: float64

8. Glossary#

- Lasso Regression#

Linear regression with L1 regularization that can set some coefficients to exactly zero (feature selection).

- Alpha (λ)#

Penalty strength in Lasso. Larger alpha increases regularization and may reduce the number of active features.

- Cross validation (CV)#

Split the data into folds, train on k‑1 folds and validate on the held‑out fold; repeat and average.

- R² (coefficient of determination)#

Measures how much variance the model explains. 1 is perfect, 0 matches the mean predictor.

- MSE#

Mean of squared errors. Sensitive to large errors.

- MAE#

Mean of absolute errors. More robust to outliers than MSE.

- Permutation importance#

Test‑time feature shuffle to estimate performance drop for each feature.

- Coefficient importance#

Weights in a linear model. In Lasso, many are shrunk to 0.

- Feature redundancy#

Two or more features carry nearly the same information (high correlation).

- GridSearchCV#

Scikit‑learn tool that evaluates parameter grids with CV and returns the best estimator.

9. Quick reference#

Common scikit‑learn patterns

Split:

train_test_split(X, y, test_size=0.2, random_state=...)CV:

KFold(n_splits=4, shuffle=True, random_state=...)Score:

cross_val_score(model, X, y, cv=kf, scoring="r2")Grid search:

GridSearchCV(model, {"alpha":[...]}, cv=kf, scoring="r2", refit=True)Metrics:

mean_squared_error,mean_absolute_error,r2_score

Diagnostic plots

Parity: predicted vs true (should hug the diagonal).

Residuals: residual vs prediction (should center near 0 without pattern).

CV curve: metric vs hyperparameter; pick the stable peak.

10. In‑class activity#

Each task uses the functions and concepts above. Fill in the ... lines.

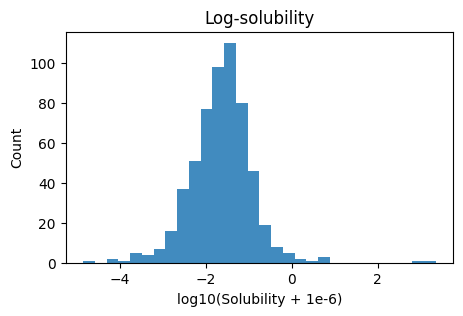

Q1. Prepare log‑solubility and visualize#

Prepare log-solubility, split 80/20 (seed=15), and visualize.

Create

y_log· = log10(Solubility_mol_per_L + 1e-6),Set

X = [MolWt, LogP, TPSA, NumRings],Split 80/20 with

random_state=15,Plot a histogram of

y_log, then a pairwise scatter matrix of the four descriptors.

Hint: After spliting, keep t

# TO DO

# y_log = ...

# X = ...

# X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y_log, test_size=0.2, random_state=15)

# Plots

# ...

Q2. Tune Ridge on the training split#

Search alphas on

np.logspace(-2, 3, 12)using 5‑fold CV on(X_tr, y_tr)Report best alpha and mean CV R², then refit

Ridge(alpha=best)on train

# TO DO

# cv = KFold(n_splits=..., shuffle=..., random_state=...)

# alphas = ...

# ...

# ...

# ridge_best = Ridge(alpha=...).fit(..., ...)

# print(f"best alpha={...:.4f} CV mean R2={max(...):.3f}")

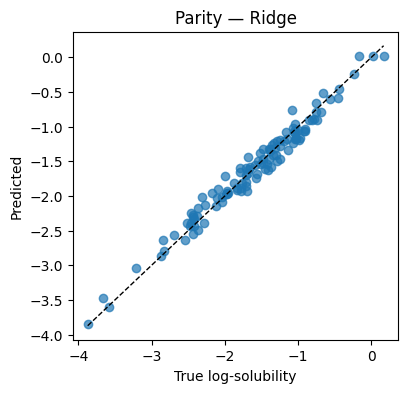

Q3. Evaluate Ridge on test and draw diagnostics#

Compute MSE, MAE, R² on

(X_te, y_te)Plot a parity plot and a residual plot

# TO DO

# y_hat = ...

# print(f"Test MSE={...:.4f} MAE={...:.4f} R2={...:.3f}")

# Parity and residual plots

# ...

Q4. Predict two new molecules (Ridge)#

Use the trained Ridge to predict log‑solubility for:

[135.0, 2.0, 9.2, 2][301.0, 0.5, 17.7, 2]

# TO DO

# X_new = np.array([[135.0, 2.0, 9.2, 2],

# [301.0, 0.5, 17.7, 2]])

# y_new = ridge_best.predict(X_new)

# print(pd.DataFrame({"MolWt": X_new[:,0], "LogP": X_new[:,1], "TPSA": X_new[:,2], "NumRings": X_new[:,3],

# "Predicted log10(solubility)": y_new}))

Q5. Interpret Ridge with coefficients and permutation importance#

Show coefficient magnitudes and signs

Compute permutation importance on the test split and plot

# TO DO

# feat = ["MolWt","LogP","TPSA","NumRings"]

# coef_ser = ...

# coef_ser.plot(kind="barh"); ...

# perm = permutation_importance(...)

# perm_ser = ...

# perm_ser.plot(kind="barh"); ...

11. Solutions#

11.1 Solution Q1#

# Log target

df_reg_mp = df_reg_mp.copy()

y_log = np.log10(df_reg_mp["Solubility_mol_per_L"] + 1e-6)

# Features and split

X = df_reg_mp[["MolWt","LogP","TPSA","NumRings"]].values

X_tr, X_te, y_tr, y_te = train_test_split(X, y_log, test_size=0.2, random_state=15)

# Plots

plt.figure(figsize=(5,3))

plt.hist(y_log, bins=30, alpha=0.85)

plt.xlabel("log10(Solubility + 1e-6)"); plt.ylabel("Count"); plt.title("Log-solubility")

plt.show()

pd.plotting.scatter_matrix(df_reg_mp[["MolWt","LogP","TPSA","NumRings"]], figsize=(5.5,5.5))

plt.suptitle("Descriptor scatter matrix", y=1.02); plt.show()

11.2 Solution Q2#

cv = KFold(n_splits=5, shuffle=True, random_state=1)

alphas = np.logspace(-2, 3, 12)

means = [cross_val_score(Ridge(alpha=a), X_tr, y_tr, cv=cv, scoring="r2").mean() for a in alphas]

best_a = float(alphas[int(np.argmax(means))])

ridge_best = Ridge(alpha=best_a).fit(X_tr, y_tr)

print(f"best alpha={best_a:.4f} CV mean R2={max(means):.3f}")

best alpha=1.8738 CV mean R2=0.968

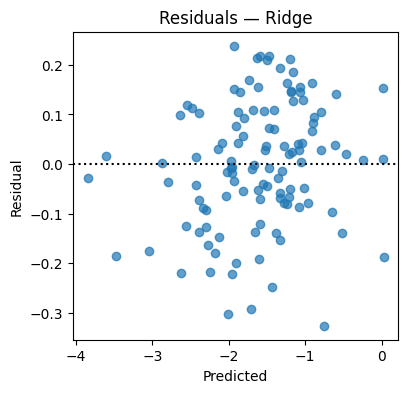

11.3 Solution Q3#

y_hat = ridge_best.predict(X_te)

print(f"Test MSE={mean_squared_error(y_te,y_hat):.4f} "

f"MAE={mean_absolute_error(y_te,y_hat):.4f} "

f"R2={r2_score(y_te,y_hat):.3f}")

plt.figure(figsize=(4.2,4))

plt.scatter(y_te, y_hat, alpha=0.7)

lims = [min(y_te.min(), y_hat.min()), max(y_te.max(), y_hat.max())]

plt.plot(lims, lims, "k--", lw=1)

plt.xlabel("True log-solubility"); plt.ylabel("Predicted"); plt.title("Parity — Ridge"); plt.show()

resid = y_te - y_hat

plt.figure(figsize=(4.2,4))

plt.scatter(y_hat, resid, alpha=0.7); plt.axhline(0, color="k", ls=":")

plt.xlabel("Predicted"); plt.ylabel("Residual"); plt.title("Residuals — Ridge"); plt.show()

Test MSE=0.0160 MAE=0.1024 R2=0.970

11.4 Solution Q4#

X_new = np.array([

[135.0, 2.0, 9.2, 2], # Molecule A

[301.0, 0.5, 17.7, 2] # Molecule B

]) # descriptors: [MolWt, LogP, TPSA, NumRings]

y_new = ridge_best.predict(X_new)

print(pd.DataFrame({

"MolWt": X_new[:,0], "LogP": X_new[:,1], "TPSA": X_new[:,2], "NumRings": X_new[:,3],

"Predicted log10(solubility)": y_new

}))

MolWt LogP TPSA NumRings Predicted log10(solubility)

0 135.0 2.0 9.2 2.0 -1.195502

1 301.0 0.5 17.7 2.0 -0.501762

11.5 Solution Q5#

feat = ["MolWt","LogP","TPSA","NumRings"]

coef_ser = pd.Series(ridge_best.coef_, index=feat).sort_values(key=np.abs, ascending=False)

print("Ridge coefficients:\n", coef_ser)

coef_ser.plot(kind="barh"); plt.gca().invert_yaxis()

plt.xlabel("Coefficient"); plt.title("Ridge coefficients"); plt.show()

perm = permutation_importance(ridge_best, X_te, y_te, scoring="r2", n_repeats=30, random_state=1)

perm_ser = pd.Series(perm.importances_mean, index=feat).sort_values()

perm_ser.plot(kind="barh"); plt.xlabel("Mean decrease in R²"); plt.title("Permutation importance on test"); plt.show()

Ridge coefficients:

LogP -0.437668

NumRings -0.002761

TPSA -0.000699

MolWt 0.000260

dtype: float64