Lecture 15 - Multi-Objective Bayesian Optimization#

Learning goals#

Connect single objective Bayesian Optimization to multiobjective problems.

Define Pareto dominance, Pareto front, scalarization, hypervolume, and expected hypervolume improvement.

Build a simple multiobjective active learning loop on a materials.

0. Setup#

1. What is multiobjective optimization#

In previous lecture, we used a surrogate model to represent an expensive experiment, then selected the next experiment using an acquisition function like Expected Improvement to iteratively find the optimized yield by tuning reaction parameter such as temperature.

We learned that we can:

Fit a surrogate on \((X, y)\).

Predict \(\mu(x)\) and \(\sigma(x)\) on candidates.

Score an acquisition \(a(x)\) (EI, UCB, PI).

Pick \(x_{next} = \arg\max a(x)\) and run the experiment.

Update data and repeat.

Today we extend that idea to multiple goals at once, for example high yield and high purity with decent reproducibility.

In multiobjective optimization we consider a vector objective $\({\bf f}(x) = \big(f_1(x), f_2(x), \ldots, f_M(x)\big).\)$

For chemical synthesis you might set

\(f_1\) as yield to maximize,

\(f_2\) as purity or selectivity to maximize,

\(f_3\) as cost to minimize or reproducibility score to maximize.

There is usually no single \(x\) that maximizes all objectives together. Instead we aim to approximate the Pareto front.

Below are a few definitions associated with this idea:

Dominance: a point \(a\) dominates \(b\) if it is at least as good on all objectives and strictly better on at least one.

Pareto set: the set of nondominated decision points.

Pareto front: the image of the Pareto set in objective space.

Hypervolume: the volume of objective space dominated by the current front relative to a reference point.

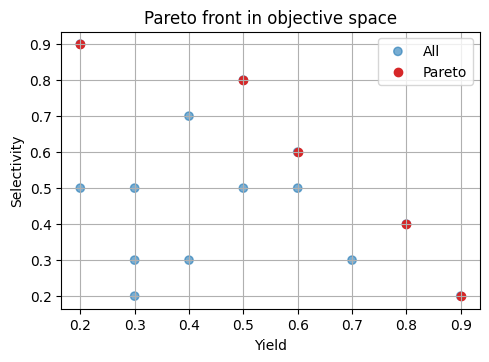

Below is a tiny 2D example:

# 1.1 Simple dominance and Pareto front in 2D

def pareto_mask(Y: np.ndarray) -> np.ndarray:

"""Return a boolean mask for nondominated rows of Y to maximize both columns."""

n = Y.shape[0]

keep = np.ones(n, dtype=bool)

for i in range(n):

if not keep[i]:

continue

dominates = np.all(Y[i] >= Y, axis=1) & np.any(Y[i] > Y, axis=1)

keep[dominates] = False

keep[i] = True

return keep

Y_demo = np.array([

[0.2, 0.9],[0.6, 0.6],

[0.9, 0.2],[0.5, 0.8],

[0.5, 0.5],[0.4, 0.7],

[0.7, 0.3],[0.8, 0.4],

[0.3, 0.3], [0.2, 0.5],

[0.6, 0.5], [0.4, 0.3],

[0.3, 0.2], [0.3, 0.5],

])

mask = pareto_mask(Y_demo)

Y_nd = Y_demo[mask]

# Visualize

plt.scatter(Y_demo[:,0], Y_demo[:,1], c=["tab:blue"]*len(Y_demo), alpha=0.6, label="All")

plt.scatter(Y_nd[:,0], Y_nd[:,1], c="tab:red", label="Pareto")

plt.xlabel("Yield")

plt.ylabel("Selectivity")

plt.title("Pareto front in objective space")

plt.legend()

plt.show()

⏰ Exercise

Add a new point [0.7, 0.6] to Y_demo, recompute the mask, and plot again. Which earlier nondominated points become dominated now?

2. Load the MOF toy dataset#

We will use the provided full factorial style synthetic dataset that mimics MOF synthesis outcomes across temperature, time, concentration, solvent, and linker choice. The file includes yield, purity, and reproducibility.

We will use a synthetic MOF dataset that records MOF synthesis outcomes across temperature, time, concentration, solvent, and linker choice. The file includes yield, purity, and reproducibility:

yieldin \([0, 0.99]\) with noise, boosts, and failures.purityin \([0, 1]\) with discontinuities.reproducibilityin \(\{0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1.0\}\).

# 2.1 Load the dataset

url = "https://raw.githubusercontent.com/zzhenglab/ai4chem/main/book/_data/mof_yield_dataset.csv"

df_raw = pd.read_csv(url)

df_raw

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

HTTPError Traceback (most recent call last)

Cell In[3], line 3

1 # 2.1 Load the dataset

2 url = "https://raw.githubusercontent.com/zzhenglab/ai4chem/main/book/_data/mof_yield_dataset.csv"

----> 3 df_raw = pd.read_csv(url)

4 df_raw

File ~\AppData\Local\Programs\Python\Python313\Lib\site-packages\pandas\io\parsers\readers.py:1026, in read_csv(filepath_or_buffer, sep, delimiter, header, names, index_col, usecols, dtype, engine, converters, true_values, false_values, skipinitialspace, skiprows, skipfooter, nrows, na_values, keep_default_na, na_filter, verbose, skip_blank_lines, parse_dates, infer_datetime_format, keep_date_col, date_parser, date_format, dayfirst, cache_dates, iterator, chunksize, compression, thousands, decimal, lineterminator, quotechar, quoting, doublequote, escapechar, comment, encoding, encoding_errors, dialect, on_bad_lines, delim_whitespace, low_memory, memory_map, float_precision, storage_options, dtype_backend)

1013 kwds_defaults = _refine_defaults_read(

1014 dialect,

1015 delimiter,

(...) 1022 dtype_backend=dtype_backend,

1023 )

1024 kwds.update(kwds_defaults)

-> 1026 return _read(filepath_or_buffer, kwds)

File ~\AppData\Local\Programs\Python\Python313\Lib\site-packages\pandas\io\parsers\readers.py:620, in _read(filepath_or_buffer, kwds)

617 _validate_names(kwds.get("names", None))

619 # Create the parser.

--> 620 parser = TextFileReader(filepath_or_buffer, **kwds)

622 if chunksize or iterator:

623 return parser

File ~\AppData\Local\Programs\Python\Python313\Lib\site-packages\pandas\io\parsers\readers.py:1620, in TextFileReader.__init__(self, f, engine, **kwds)

1617 self.options["has_index_names"] = kwds["has_index_names"]

1619 self.handles: IOHandles | None = None

-> 1620 self._engine = self._make_engine(f, self.engine)

File ~\AppData\Local\Programs\Python\Python313\Lib\site-packages\pandas\io\parsers\readers.py:1880, in TextFileReader._make_engine(self, f, engine)

1878 if "b" not in mode:

1879 mode += "b"

-> 1880 self.handles = get_handle(

1881 f,

1882 mode,

1883 encoding=self.options.get("encoding", None),

1884 compression=self.options.get("compression", None),

1885 memory_map=self.options.get("memory_map", False),

1886 is_text=is_text,

1887 errors=self.options.get("encoding_errors", "strict"),

1888 storage_options=self.options.get("storage_options", None),

1889 )

1890 assert self.handles is not None

1891 f = self.handles.handle

File ~\AppData\Local\Programs\Python\Python313\Lib\site-packages\pandas\io\common.py:728, in get_handle(path_or_buf, mode, encoding, compression, memory_map, is_text, errors, storage_options)

725 codecs.lookup_error(errors)

727 # open URLs

--> 728 ioargs = _get_filepath_or_buffer(

729 path_or_buf,

730 encoding=encoding,

731 compression=compression,

732 mode=mode,

733 storage_options=storage_options,

734 )

736 handle = ioargs.filepath_or_buffer

737 handles: list[BaseBuffer]

File ~\AppData\Local\Programs\Python\Python313\Lib\site-packages\pandas\io\common.py:384, in _get_filepath_or_buffer(filepath_or_buffer, encoding, compression, mode, storage_options)

382 # assuming storage_options is to be interpreted as headers

383 req_info = urllib.request.Request(filepath_or_buffer, headers=storage_options)

--> 384 with urlopen(req_info) as req:

385 content_encoding = req.headers.get("Content-Encoding", None)

386 if content_encoding == "gzip":

387 # Override compression based on Content-Encoding header

File ~\AppData\Local\Programs\Python\Python313\Lib\site-packages\pandas\io\common.py:289, in urlopen(*args, **kwargs)

283 """

284 Lazy-import wrapper for stdlib urlopen, as that imports a big chunk of

285 the stdlib.

286 """

287 import urllib.request

--> 289 return urllib.request.urlopen(*args, **kwargs)

File ~\AppData\Local\Programs\Python\Python313\Lib\urllib\request.py:189, in urlopen(url, data, timeout, context)

187 else:

188 opener = _opener

--> 189 return opener.open(url, data, timeout)

File ~\AppData\Local\Programs\Python\Python313\Lib\urllib\request.py:495, in OpenerDirector.open(self, fullurl, data, timeout)

493 for processor in self.process_response.get(protocol, []):

494 meth = getattr(processor, meth_name)

--> 495 response = meth(req, response)

497 return response

File ~\AppData\Local\Programs\Python\Python313\Lib\urllib\request.py:604, in HTTPErrorProcessor.http_response(self, request, response)

601 # According to RFC 2616, "2xx" code indicates that the client's

602 # request was successfully received, understood, and accepted.

603 if not (200 <= code < 300):

--> 604 response = self.parent.error(

605 'http', request, response, code, msg, hdrs)

607 return response

File ~\AppData\Local\Programs\Python\Python313\Lib\urllib\request.py:533, in OpenerDirector.error(self, proto, *args)

531 if http_err:

532 args = (dict, 'default', 'http_error_default') + orig_args

--> 533 return self._call_chain(*args)

File ~\AppData\Local\Programs\Python\Python313\Lib\urllib\request.py:466, in OpenerDirector._call_chain(self, chain, kind, meth_name, *args)

464 for handler in handlers:

465 func = getattr(handler, meth_name)

--> 466 result = func(*args)

467 if result is not None:

468 return result

File ~\AppData\Local\Programs\Python\Python313\Lib\urllib\request.py:613, in HTTPDefaultErrorHandler.http_error_default(self, req, fp, code, msg, hdrs)

612 def http_error_default(self, req, fp, code, msg, hdrs):

--> 613 raise HTTPError(req.full_url, code, msg, hdrs, fp)

HTTPError: HTTP Error 404: Not Found

The reaction parameters include:

temperature (°C): 10 levels ->

[25, 40, 55, 70, 85, 100, 115, 130, 155, 160]time_h (hours): 10 levels ->

[12, 24, ..., 120]concentration_M (M): 10 levels ->

[0.05, 0.10, ..., 0.50]solvent_DMF: one-hot binary {

0=H2O,1=dimethyl foramide}organic linker (10 choices), such as

Fumaric acid,Trimesic acid, andBenzimidazole.

3. Feature engineering for multiobjective modeling#

We will build a light feature set using both synthesis conditions and molecular structure information. This compact design provides chemical and process context without relying on heavy cheminformatics toolkits.

3.1 Minimal numeric features#

We begin with numeric synthesis parameters that directly influence material outcomes:

temperature, time_h, concentration_M, and solvent_DMF.

These are copied into a numeric feature frame:

num_cols = ["temperature", "time_h", "concentration_M", "solvent_DMF"]

X_num = df[num_cols].astype(float).copy()

X_num

3.2 One-hot encoding for SMILES#

The SMILES column lists discrete molecular structures. To make this information usable by machine learning models, we convert it into a numeric form through one-hot encoding.

One-hot encoding creates a binary vector for each category:

Each unique SMILES gets its own column.

A value of

1marks the presence of that molecule in a given row, and0otherwise.

This prevents the model from interpreting SMILES identifiers as ordinal numbers while preserving molecular identity.

from sklearn.preprocessing import OneHotEncoder

# Define encoder

enc = OneHotEncoder(sparse_output=False, handle_unknown='ignore')

# Fit and transform SMILES into binary vectors

smiles_encoded = enc.fit_transform(df[['smiles']])

# Retrieve encoded column names

smiles_feature_names = enc.get_feature_names_out(['smiles'])

# Build DataFrame for encoded SMILES

X_smiles = pd.DataFrame(smiles_encoded, columns=smiles_feature_names, index=df.index)

# Combine numeric and encoded features

X = pd.concat([X_num, X_smiles], axis=1)

print(X.shape, X.columns[:10].tolist())

X.head(3)

3.3 Targets for multiobjective learning#

We will form a 3 objective vector:

\(f_1\):

yieldto maximize.\(f_2\):

purityto maximize.\(f_3\): numeric reproducibility where higher is better.

# 3.4 Target matrix

Y = df[["yield","purity","reproducibility"]].astype(float).values

print(Y.min(axis=0), Y.max(axis=0))

Y

4. Pareto utilities and hypervolume in 2D#

This section builds intuition for multiobjective comparison using two outcomes at a time before returning to three.

We use \(f_1=\) = yield and \(f_2=\) = purity. The goal is to identify the subset of experiments that are not outperformed by any other experiment across both objectives. These are the candidates on the Pareto front. Working in 2D makes it easy to see which points survive and how much area of the objective space they dominate relative to a chosen reference.

Note

Note that in reality, we usually start with only a couple of experiments. So we will show the case for both 50 experiment and the full dataset (20000 experiments).

Now let’s look at the full dataset. Again, note that in reality you will not be able to see this “final answer.”

Next, we talk about an important idea, hypervolume (HV) which is the volume of the dominated region bounded by a reference point \(r\). It is a way to measure how much of the “good” region of objective space is covered by your Pareto front. In two objectives (for example, yield and purity), each experiment corresponds to a point. The Pareto front marks those points that are not outperformed by any other in both metrics. The hypervolume is then the total area (or volume in higher dimensions) between that front and a chosen reference point.

Note

You can think of it as the portion of the map where the model or experiments are doing well. If your Pareto front moves outward toward higher yield and purity, the dominated region expands, and the hypervolume increases. A larger hypervolume means better overall trade offs across objectives.

The reference point defines the lower bound of the region you measure against. It must be worse than all observed points in every objective because hypervolume represents improvement relative to that point. For yield and purity, which are maximized, this means picking a reference near the bottom left corner of the plot.

If all your data are normalized between 0 and 1, the natural choice is (0, 0) — representing the absolute worst case (zero yield, zero purity). You can also use (0.2, 0.2) or another slightly higher reference if you want to focus only on improvements beyond a minimum acceptable performance threshold. That reference would mean: “We only care about the area above 20% yield and 20% purity.”

Let’s assume we run 3 additional experiments and we are so lucky that they achieve strong outcomes around high yield and purity ([0.90, 0.80, 0.70], [0.92, 0.78, 0.75], and [0.88, 0.82, 0.65]).

We can take a look at the change to the hypervolume:

From above plot, we see that the hypervolume increase equals the additional “good” region covered by the improved front. Using the same reference point keeps comparisons fair. In synthesis terms, this reflects the net expansion of acceptable performance space when higher yield and purity conditions are discovered.

We can compare with the full dataset, and this give you an idea of the maxiumn hypervolume you can achieve. But, again, keep in mind that the entire space / synthesis-yield relationship is usually a blackbox function and you won’t know the max hypervolume.

5. Scalarization and surrogate models for each objective#

A common way to turn multiple objectives into one is weighted sum: $\( s_w(x) = \sum_{j=1}^m w_j \,\tilde f_j(x) \)\( with \)w_j \ge 0\( and \)\sum_j w_j = 1\(, where \)\tilde f_j$ are normalized objectives. This is fast and easy to implement.

Caution: linear scalarization can miss non-convex parts of the Pareto front. Still, it is a practical baseline and pairs well with BO.

We now assume we only have a 50 point subset in hand. All modeling, selection, and validation in this section uses only X50 and Y50. The idea is simple: fit one surrogate per objective on the training split of these 50 points, evaluate on the held out split, and then use a scalarized acquisition to propose new experiments from the same 50 point design space.

5.1 Train test split and scaling#

Y50 = Y[idx_50]

X50 = np.asarray(X)[idx_50]

# Train test split within the 50 points

X_train, X_test, Y_train, Y_test = train_test_split(

np.asarray(X50), np.asarray(Y50), test_size=0.2, random_state=0

)

# Standardize features using only training data

scaler_X = StandardScaler().fit(X_train)

Xtr = scaler_X.transform(X_train)

Xte = scaler_X.transform(X_test)

Ytr = Y_train.copy()

Yte = Y_test.copy()

Xtr.shape, Ytr.shape

5.2 Three GPs with Matern on the 50 point split#

Here we fit one GP per objective on Xtr, Ytr. We use a Matern kernel with a small white noise term for numerical stability. Scores are printed on Xte, Yte. GPs are flexible and give calibrated uncertainties for acquisition functions. On larger feature sets they can be slow, which is why we also show Random Forests.

Note

Recall, the kernel is a function that defines the covariance or similarity between data points, determining how the Gaussian Process generalizes from the training data.

from sklearn.gaussian_process import GaussianProcessRegressor

from sklearn.gaussian_process.kernels import Matern, ConstantKernel as C, WhiteKernel

from sklearn.metrics import r2_score, mean_absolute_error

kernel = C(1.0) * Matern(length_scale=1.0, nu=2.5) + WhiteKernel(noise_level=1e-3)

gps = []

for m in range(Ytr.shape[1]):

gpr = GaussianProcessRegressor(kernel=kernel, normalize_y=True, n_restarts_optimizer=2, random_state=m)

gpr.fit(Xtr, Ytr[:, m])

gps.append(gpr)

for m, name in enumerate(["yield", "purity", "reproducibility"]):

pred = gps[m].predict(Xte)

print(name, "R2:", r2_score(Yte[:, m], pred), "MAE:", mean_absolute_error(Yte[:, m], pred))

5.3 RF trio trained only on the 50 point split#

Here we train three RF models on Xtr, Ytr and score on Xte, Yte. RFs scale well and give a simple uncertainty proxy from the spread across trees, which we will use for acquisition.

from sklearn.ensemble import RandomForestRegressor

from sklearn.metrics import r2_score, mean_absolute_error

rfs = []

for m in range(Ytr.shape[1]):

rf = RandomForestRegressor(

n_estimators=300,

min_samples_leaf=5,

random_state=10 + m,

n_jobs=-1

)

rf.fit(Xtr, Ytr[:, m])

rfs.append(rf)

for m, name in enumerate(["yield", "purity", "reproducibility"]):

pred = rfs[m].predict(Xte)

print(name, "R2:", r2_score(Yte[:, m], pred), "MAE:", mean_absolute_error(Yte[:, m], pred))

We see that due to limited data size, both GP and RF surrogate models have a poor R2 value.

Note

Use RF surrogates when the dataset is larger or when GP training is slow. RF also gives a simple uncertainty proxy from the spread across trees, which we will use later for bandit style decisions.

6. Acquisition for multiobjective BO#

We now simulate planning within the 50 point space. Think of each of the 50 rows as a candidate experiment. At each iteration we will:

fit the three RF surrogates on the experiments already “run” (a small seed set from the 50),

evaluate a scalarized acquisition on a candidate cloud sampled from

Xtr,propose the single best next point, and

emulate an outcome by nearest neighbor lookup inside the same 50 point training pool.

This is a pool based simulation that stays within the 50 points you actually have. We also track an approximate 3D hypervolume of the observed set, using a crude Monte Carlo estimate in the unit cube for quick feedback.

# Utilities for candidate cloud and scalarized EI

from typing import Tuple

from scipy.stats import norm

def candidate_cloud(Xbase: np.ndarray, n: int = 2000, seed: int = 0) -> np.ndarray:

rng = np.random.RandomState(seed)

idx = rng.choice(Xbase.shape[0], size=min(n, Xbase.shape[0]), replace=False)

return Xbase[idx]

def rf_mu_sigma(model: RandomForestRegressor, Xc: np.ndarray) -> Tuple[np.ndarray, np.ndarray]:

preds = np.stack([est.predict(Xc) for est in model.estimators_], axis=1)

return preds.mean(axis=1), preds.std(axis=1) + 1e-6

def ei_from_mu_sigma(mu: np.ndarray, sd: np.ndarray, best: float, xi: float = 0.01) -> np.ndarray:

sd = np.maximum(sd, 1e-12)

z = (mu - best - xi) / sd

return (mu - best - xi) * norm.cdf(z) + sd * norm.pdf(z)

def sample_simplex(M: int) -> np.ndarray:

return np.random.dirichlet(alpha=np.ones(M))

def hv_approx_3d(Ym: np.ndarray, ref: np.ndarray, n_ref: int = 4000, seed: int = 0) -> float:

# crude Monte Carlo hypervolume estimate over [ref, 1]^3 for maximization

rng = np.random.RandomState(seed)

U = rng.uniform(low=ref, high=np.array([1, 1, 1]), size=(n_ref, 3))

mask = np.zeros(n_ref, dtype=bool)

for y in Ym[nondominated_mask(Ym)]:

mask |= np.all(U <= y, axis=1)

return mask.mean() * np.prod(1 - ref)

# Run a few scalarized BO steps on the 50 point pool

rng = np.random.RandomState(7)

# Candidate cloud drawn from the 50 point training pool

Xc = candidate_cloud(Xtr, n=2000, seed=2)

# Start with 8 random seed experiments from the 50 training rows

seed_idx = rng.choice(Xtr.shape[0], size=8, replace=False)

D_X = Xtr[seed_idx]

D_Y = Ytr[seed_idx]

history_hv = []

ref_point = np.array([0.0, 0.0, 0.0])

# Track initial HV

history_hv.append(hv_approx_3d(D_Y, ref_point, n_ref=5000, seed=1))

n_rounds = 3 # you can change it to 15, for html purpose we use 3

for t in range(n_rounds):

# Refit RF surrogates on the current observed subset

for m in range(3):

rfs[m].fit(D_X, D_Y[:, m])

# Predict mean and uncertainty on the candidate cloud

mu_list, sd_list = [], []

for m in range(3):

mu_m, sd_m = rf_mu_sigma(rfs[m], Xc)

mu_list.append(mu_m); sd_list.append(sd_m)

MU = np.column_stack(mu_list)

SD = np.column_stack(sd_list)

# Random scalarization weights on the simplex

w = sample_simplex(3)

# Scalarized mean and scalarized EI baseline

g_mu = MU @ w

mu_D = np.column_stack([rfs[m].predict(D_X) for m in range(3)])

best_g = float((mu_D @ w).max())

# Scalarized uncertainty under independence approximation

g_sd = np.sqrt(np.maximum(1e-8, np.sum((SD * w) ** 2, axis=1)))

# EI on scalarized surrogate

acq = ei_from_mu_sigma(g_mu, g_sd, best=best_g, xi=0.01)

# Pick next candidate

j = int(np.argmax(acq))

x_next = Xc[j:j+1]

# Emulate measurement by nearest neighbor in the 50 training pool

k = int(np.argmin(np.linalg.norm(Xtr - x_next, axis=1)))

y_next = Ytr[k:k+1]

# Update observed set

D_X = np.vstack([D_X, x_next])

D_Y = np.vstack([D_Y, y_next])

# Track 3D HV

hv_now = hv_approx_3d(D_Y, ref_point, n_ref=3000, seed=100 + t)

history_hv.append(hv_now)

print("Observed points:", D_X.shape[0], "Final approx HV:", history_hv[-1])

We seed with a handful of points from Xtr, Ytr. Each round we refit the RF trio on the current observed set, score a candidate cloud from Xtr using random scalarization with EI, pick the best candidate, and emulate the measurement by nearest neighbor lookup inside Xtr to fetch its Ytr. Hypervolume in 3D is tracked after each addition.

The curve below shows how the approximate 3D hypervolume grows as the loop adds points selected by random scalarization with EI. This is a quick way to judge whether the front is expanding within the 50 point design space.

7. End to end MOBO loop on the MOF dataset#

We now put everything together as a small, complete multiobjective active learning loop that starts from 50 points and grows by proposing 10 new points per round for 15 rounds. The goal is to expand the Pareto set over yield, purity, and reproducibility while tracking a clear 2D hypervolume on yield and purity.

Choices in this section:

Surrogate: one Gaussian Process per objective

Acquisition: random candidate cloud, scalarization with fixed equal weights, and Expected Improvement on the scalarized objective

Weights: fixed at

[0.33, 0.33, 0.33]for the entire run to keep behavior easy to interpretEvaluation: adding the selected pool rows directly, which emulates running the real experiments

We will show the following results:

Iteration prints with the scalarized EI top scores

The three best proposed conditions per round

A four panel figure with hypervolume trace and per objective best so far curves

A separate plot comparing the yield vs purity Pareto front at the start and at the end

Above we define the function (click to see more details) and below we run everything togther with fixed weights, 15 rounds, 10 picks/round:

results = run_mobo_with_oracle(

search_space=search_space,

run_experiment=run_experiment,

initial_idx=initial_idx,

weights=np.array([0.33, 0.33, 0.33]),

rounds=20,

batch=10,

cloud=6000,

ref_2d=(0.0, 0.0),

rng_seed=17

)

We can plot the results:

Finally, we want to run the same MOBO loop four times per surrogate type (GP and RF), one for each acquisition: EI, UCB, PI, and greedy mean. The loop proposes only from the discrete search_space, gets outcomes only through run_experiment(choice), and never reads targets from the dataframe. We track the user-defined scalarized value (fixed weights [0.33, 0.33, 0.33]) over iterations.

traces = compare_rf_gp_acq_8panels(

search_space=search_space,

run_experiment=run_experiment,

initial_idx=initial_idx, # 50 starting indices in search_space

rounds=15,

batch=10,

cloud=6000,

weights=np.array([0.33, 0.33, 0.33]),

rng_seed=42,

kappa=1.0,

xi=0.01

)

Below, we will see when we change the weights, the MOBO will pay attention to objectives with higher weights and results can be different.

traces2 = compare_rf_gp_acq_8panels(

search_space=search_space,

run_experiment=run_experiment,

initial_idx=initial_idx, # 50 starting indices in search_space

rounds=15,

batch=10,

cloud=6000,

weights=np.array([0.8, 0.15, 0.05]), #care more on reaction yield

rng_seed=42,

kappa=1.0,

xi=0.01

)

8. Glossary#

- Pareto dominance#

Point \(a\) dominates \(b\) if \(a\) is at least as good on all objectives and strictly better on one.

- Pareto front#

The set of nondominated objective vectors. Moving along the front trades objectives.

- Scalarization#

Combine multiple objectives into one with weights \(w_m \ge 0\) and \(\sum w_m = 1\) to apply single objective methods.

- Hypervolume#

Measure of the volume dominated by the current Pareto front compared to a reference point. Larger is better.

- Expected Hypervolume Improvement#

Acquisition used in multiobjective BO that prefers candidates expected to increase hypervolume.

9. In-class activity#

Q1. Build a tiny BO “coach” with an LLM#

Use an LLM (ChatGPT or Claude) as your coding buddy to create a function in Colab or a small UI that runs Bayesian Optimization (BO) on a reaction you choose. You define the variable space and the objectives, feed a few data points, and your tool suggests 3 new experiments. After you run them, you type in the results and the tool updates, ready to suggest 3 more.

What you will produce out of this activity: A function that:

choose the reaction family and define the variable space

input your measured results

Output “Suggest 3” to get the next batch

Support “Add results” to append new data and keep going

Suggested scope Pick one of the following case:

Organic reaction screening

Catalysis screening

Liquid nanoparticle synthesis

MOF or polymer synthesis

Keep the variable space small at first. For example:

temperature in {25, 50, 75, 100}

time in {1, 2, 4}

solvent flag in {0, 1}

catalyst choice in {A, B, C} Your objectives can be one or more of: yield, particle size, selectivity.

Interaction rules for the BO tool

You input 3 measured points → tool suggests 3

You input 9 measured points → tool suggests 3

You can append results anytime and resuggest

Stay within your discrete grid. Suggestions must be valid choices from your space

Note

Hint: Below are examples of prompts you can give to an LLM to generate code.

Version A (simpler):

LLM output code from Version A prompt:

Now we can also consider Version B (more features), with UI and bottons for someone who does not code in your lab to use:

LLM output code from Version B prompt: