Lecture 16 - Reinforcement Learning#

Learning goals#

Understand the definition of agent, environment, state, action, reward, trajectory, policy, and value.

Build a tiny grid world with a chemistry flavor and implement tabular Q-learning step by step.

Compare exploration strategies such as epsilon greedy, optimistic starts, UCB1, and Thompson sampling in bandits.

0. Setup#

1. Reinforcement learning concepts#

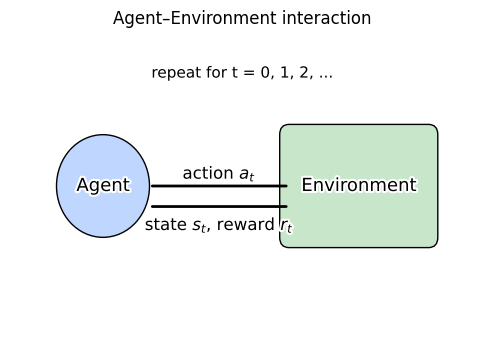

Reinforcement learning studies decision making through repeated interaction.

An agent observes a state \(s\), chooses an action \(a\), gets a reward \(r\), and moves to a new state \(s'\).

The aim is to maximize expected return \(G = r_0 + \gamma r_1 + \gamma^2 r_2 + \cdots\) with \(\gamma \in [0,1)\).

For example, in closed-loop chemistry discovery the agent proposes the next experiment and the environment is the lab system that reports outcomes like yield.

Here are key terms:

State \(s\): summary of what matters right now.

Action \(a\): a choice such as a set of synthesis conditions.

Reward \(r\): scalar signal such as yield or a utility of yield and purity.

Policy \(\pi(a\mid s)\): a rule to pick actions given a state.

Value \(V^{\pi}(s)\): expected return from state \(s\) under policy \(\pi\).

Action value \(Q^{\pi}(s,a)\): expected return if we choose \(a\) in \(s\) then follow \(\pi\).

Model: transition and reward dynamics, often unknown in labs.

The next plot shows this loop visually.

2. Let’s play games to understand Q-Learning!#

One of the simplest ways of doing Reinforcement Learning is called Q-learning. Here we want to estimate so-called Q-values which are also called action-values, because they map a state of the game-environment to a numerical value for each possible action that the agent may take. The Q-values indicate which action is expected to result in the highest future reward, thus telling the agent which action to take.

Most of time, we do not know what the Q-values are supposed to be, so we first initialize all to zero and then updated repeatedly as new information is collected from the agent playing the game. When update the Q-valu, we consider discount-factor slightly below 1, which this causes more distant rewards (e.g. take 10 steps to get 1 point vs. take 2 step to get 1 point) to contribute less to the Q-value, thus making the agent favour rewards that are closer in time.

Therefore, the formula for updating the Q-value is:

Q-value for state and action = reward + discount * max Q-value for next state

Next, we’ll play interactive “games” that make these updates visible.

2.1 Interactive Game 1 — Breakout#

State

Binned ball and paddle positions plus ball velocity signs.

Actions

Left, Stay, Right.

Controls

← / → or A / D to move the paddle.

Try manual mode first.

Enable Agent in the panel to let Q-learning play automatically.

Adjust:

ε (epsilon): exploration rate

α (alpha): learning rate

γ (gamma): discount factor

Rewards

+1 for breaking a brick

+0.01 for hitting the ball with the paddle

−1 for losing a life

−0.001 per step to encourage faster play

Try training for several episodes and then watch the agent’s learned behavior.

Reinforcement Learning demo

+1 for breaking a brick, +0.01 for paddle hits, -1 for losing a life, and a tiny -0.001 per step.

State: binned ball x, paddle x, ball vx sign, ball vy sign.

Actions: Left, Stay, Right.

ε-greedy Q-learning: Q(s,a) ← Q + α[r + γ max_a' Q(s',a') - Q].

⏰ Exercise

Use very large or small ɛ̝ and γ values (e.g. 0 and 1) to see any changes on the agent’s behaviour.

2.2 Interactive Game 2 — Maze#

In this grid world, each cell is a state, and the agent learns to reach the goal.

Reward:

−1 per move, +100 at the goal → shorter paths yield higher return

Actions:

Up, Down, Left, Right

Learning rule:

$\(

Q(s,a) \leftarrow Q(s,a) + \alpha [r + \gamma \max_{a'} Q(s',a') - Q(s,a)]

\)$

Enable the agent, train for multiple episodes, and observe how the route shortens over time.

Reinforcement Learning demo

-1 every time step and +100 at the goal. Shorter paths earn higher return.State: grid cell (x,y). Actions: Up, Down, Left, Right.

ε-greedy Q-learning:

Q(s,a) ← Q(s,a) + α[r + γ max_a' Q(s',a') − Q(s,a)].

⏰ Exercise

Try ɛ̝ = 0 or γ = 0 with any learning rate, what do you see?

2.3 Interactive Game 3 — Reaction Surface Screening#

2.3 Interactive Game 3 — Reaction Surface Screening#

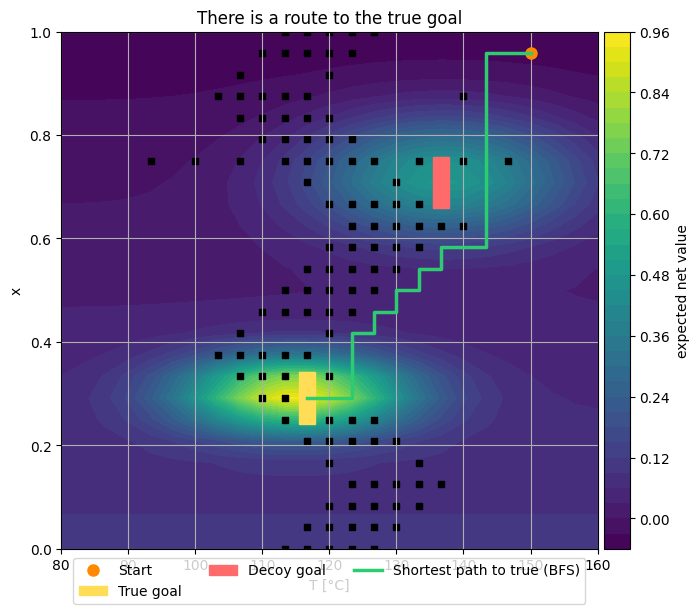

This environment resembles a reaction optimization problem.

Cells represent combinations of temperature \(T\) and composition \(x\).

There are:

Walls (black) that block motion

A true optimum (yellow) with reward \(100\)

A decoy optimum (red) with reward \(-50\)

Every step costs −1.

The agent uses ε-greedy Q-learning to find the best route.

Watch how, after enough training, it learns to avoid the decoy and reach the true goal.

Define wall map (0 = wall, 1 = open)

Reinforcement Learning demo

Q(s,a) ← Q(s,a) + α[r + γ max_a' Q(s',a') − Q(s,a)].

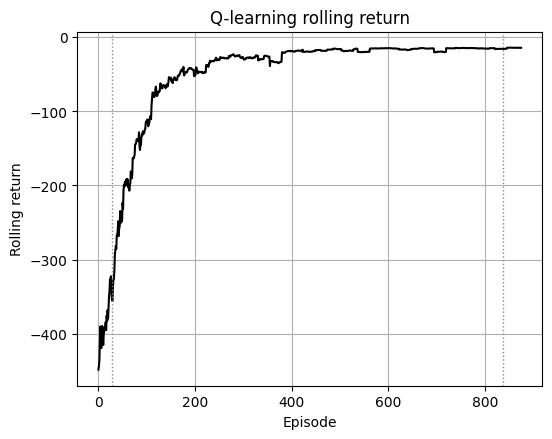

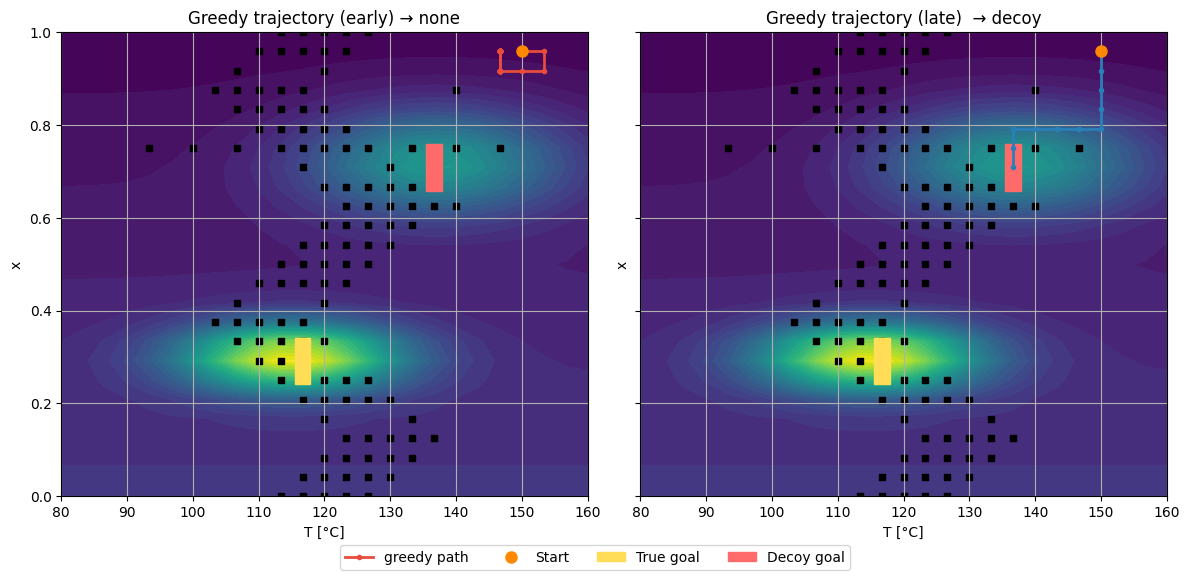

3. Q-learning on a Chemistry Grid#

Similar to the Demo 3, this part we build a \((T,x)\) grid environment in Python.

It places two reward peaks (true and decoy) and scripted walls separating regions.

We train tabular Q-learning with decaying ε and compare:

Early Q-table: prefers the nearby decoy (shorter but worse path)

Late Q-table: learns the long path to the true optimum

Why? Early training underestimates distant rewards.

As updates propagate, the agent learns that long paths with small penalties lead to higher return overall.

true goal: (np.int64(11), np.int64(7)) decoy: (17, 17)

Early training has fewer updates. The path to the true goal is long and costs many -1 steps before the +100 reward at the goal.

The decoy has a terminal penalty (for example −50) but may sit behind short corridors. Early Q often overestimates short routes and underestimates long ones. Greedy on an undertrained Q picks the locally better-looking path, which is often the decoy.

Note

With more episodes the updates push up Q along the route to the true goal and push down Q around the decoy due to its terminal penalty. Then greedy flips to the true route.

4. Bridge to Multi-Armed Bandits#

In chemical research we often choose the next experiment anywhere in the space, informed by past data (as in Bayesian optimization and active learning we learned in the previous lecture). Unlike a reinforcement learning (RL) grid world shown above, in practice it’s less frequent that we move only to neighboring conditions (like “up”, “down”, “left”, “right”) after each reaction.

Instead, every experiment can be any point in the search space.

Because there is no meaningful notion of “current position” (enviroment), we can simplify the RL setup:

there is effectively only one state that repeats each round.

This simplification leads to the multi-armed bandit formulation.

Under this one-state bandit setting, think about doing experiment in your lab like going to casino, we have \(K\) possible actions (arms), each representing an experimental condition such as a catalyst, solvent, or temperature combination.

Each arm \(i\) has an unknown expected reward \(\mu_i\) (e.g., expected yield) for different reactions (for example, reaction time 12h give an average reaction yield for suzuki coupling on 70% for 100 substrates, while 200C only give 10% success rate for the same pool of substrates).

At each trial \(t = 1, 2, \dots, T\):

Select an arm \(A_t \in \{1, \dots, K\}\)

Observe a reward \(R_t\) drawn from a distribution with mean \(\mu_{A_t}\)

Update your estimates based on what you learned

The objective is to maximize the total reward:

or equivalently, to minimize the regret, which measures how much we lose compared to always picking the best arm:

Below is a mini-game to give you an idea of this:

Each arm (catalyst or condition) is like a slot machine with an unknown payout probability.

You can pull one arm per round — that’s one experiment.

After observing the outcome (success or yield), update your belief about that arm.

Decide whether to explore new arms or exploit the best one so far.

ChemLab: explore vs exploit

You are screening catalysts for a reaction. Each catalyst has an unknown success rate (yield). You can run one experiment per round. Try a strategy: explore new catalysts to learn their true performance or exploit the best one you know so far. Compare strategies and watch how average yield and regret evolve.

Below are the equations we use for the above examples:

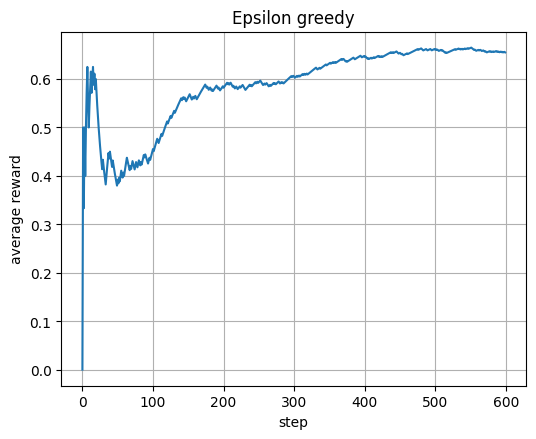

ε-greedy: explore random arm with prob ε, otherwise pick highest mean estimate.

est = s/n is average reward per arm; we update counts each step.

avg is cumulative average reward over time.

means = np.array([0.78, 0.72, 0.48, 0.44, 0.36, 0.30, 0.25, 0.18], dtype=float) #cat A to H

K = len(means)

def pull(arm, rng):

return float(rng.binomial(1, means[arm]))

# ε-greedy (simple math: est = s/n, pick max; cum avg = total/t)

def run_eps_greedy(T=600, eps=0.1, seed=2):

rng = np.random.default_rng(seed)

n = np.zeros(K, int); s = np.zeros(K, float)

avg = []; total = 0.0

for t in range(1, T+1):

if rng.random() < eps:

a = int(rng.integers(0, K))

else:

est = s / np.maximum(1, n)

ties = np.flatnonzero(est == est.max())

a = int(rng.choice(ties))

r = pull(a, rng); n[a] += 1; s[a] += r; total += r

avg.append(total / t)

return np.array(avg), n, s

avg_e, n_e, s_e = run_eps_greedy()

plt.plot(avg_e); plt.xlabel("step"); plt.ylabel("average reward"); plt.title("Epsilon greedy"); plt.show()

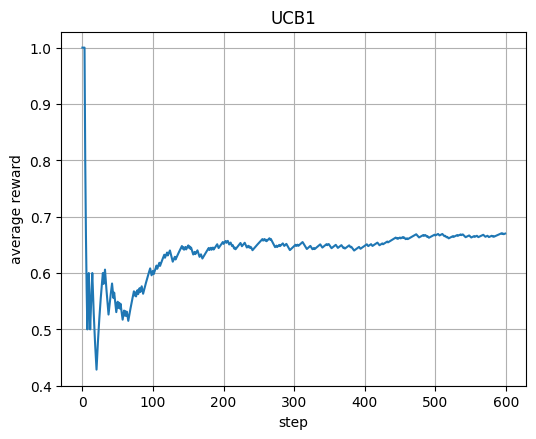

UCB1: each arm starts once; after that use est + sqrt(2 ln t / n).

This bonus term encourages early exploration and later exploitation.

avg shows how the average reward improves over time.

# UCB1 (simple math: est = s/n, bonus = sqrt(2 ln t / n); cum avg)

def run_ucb1(T=600, seed=3):

rng = np.random.default_rng(seed)

n = np.zeros(K, int); s = np.zeros(K, float)

avg = []; total = 0.0

# pull each arm once

for a in range(K):

r = pull(a, rng); n[a] += 1; s[a] += r; total += r

avg.append(total / (a+1))

# then UCB

for t in range(K+1, T+1):

est = s / n

bonus = np.sqrt(2.0 * np.log(t) / n)

a = int(np.argmax(est + bonus))

r = pull(a, rng); n[a] += 1; s[a] += r; total += r

avg.append(total / t)

return np.array(avg), n, s

avg_u, n_u, s_u = run_ucb1()

plt.plot(avg_u); plt.xlabel("step"); plt.ylabel("average reward"); plt.title("UCB1"); plt.show()

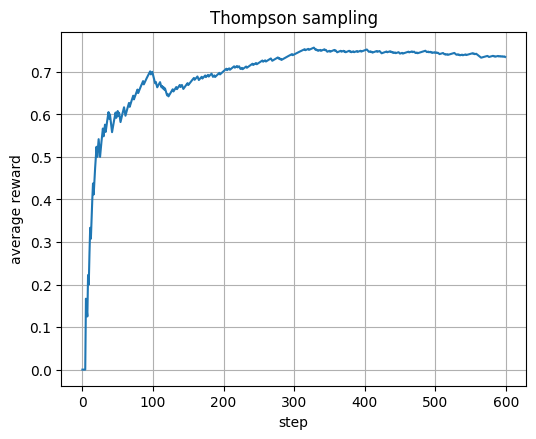

Thompson sampling: each arm has Beta(a,b) belief; sample, pick highest.

Update a+=r (success) and b+=(1−r) (failure) each step.

avg shows how Bayesian exploration converges to best catalyst.

# Thompson (simple math: Beta(a,b); sample; update a+=r, b+=(1-r); cum avg)

def run_thompson(T=600, seed=4):

rng = np.random.default_rng(seed)

a_cnt = np.ones(K); b_cnt = np.ones(K)

avg = []; total = 0.0

for t in range(1, T+1):

samples = rng.beta(a_cnt, b_cnt)

a = int(np.argmax(samples))

r = pull(a, rng); total += r

a_cnt[a] += r; b_cnt[a] += (1.0 - r)

avg.append(total / t)

return np.array(avg), a_cnt, b_cnt

avg_t, a_t, b_t = run_thompson()

plt.plot(avg_t); plt.xlabel("step"); plt.ylabel("average reward"); plt.title("Thompson sampling"); plt.show()

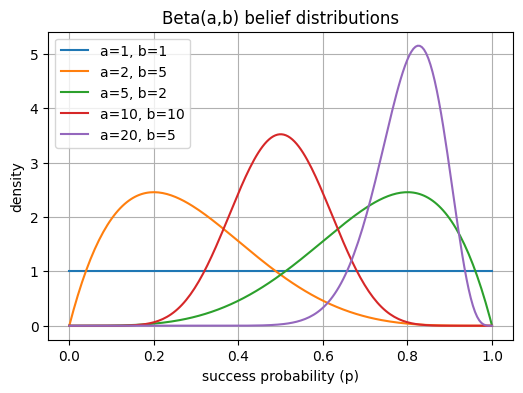

Beta(a,b) belief:

Each curve below shows how the distribution changes as successes (a) and failures (b) grow.

High a → belief shifts toward 1.

High b → belief shifts toward 0.

Beta(1,1) is uniform (complete uncertainty).

Beta(1,1) → flat line (no knowledge yet).

Beta(5,2) → skewed right (we’ve seen mostly successes).

Beta(2,5) → skewed left (mostly failures).

As counts rise (e.g., Beta(20,5)), the curve narrows — higher confidence in the estimate.

5. Case study: MOF synthesis as a bandit on yield#

We will use the synthetic MOF dataset we seen in the last lecture. It records outcomes for combinations of temperature, time, concentration, solvent identity, and the organic linker.

For this version we focus on yield only in the range [0, 1]. The goal is to find general synthesis conditions that give high yield for each of 10 linkers.

The dataset acts as our simulator. Each time the bandit chooses a recipe the simulator samples a matching row and returns its yield.

Note

For this section, please use Google Colab to run. Below only code is shown.

5.1 Load and process the dataset#

# Load full dataset

url = "https://raw.githubusercontent.com/zzhenglab/ai4chem/main/book/_data/mof_yield_dataset.csv"

df_raw = pd.read_csv(url)

# Pick the 10 most frequent linkers so each has adequate coverage in the table

top_linkers = df_raw['smiles'].value_counts().head(10).index.tolist()

def linker_actions(df_like, linker):

"""All condition tuples that actually exist for this linker."""

sub = df_like[df_like['smiles'] == linker]

acts = (

sub[['temperature','time_h','concentration_M','solvent_DMF']]

.drop_duplicates()

.itertuples(index=False, name=None)

)

return list(acts)

def make_pull_yield(df_like, linker, acts):

"""

Return a function pull(action, rng) -> yield in [0,1], sampling from rows observed for this linker+action.

If an action is not present for the linker it is skipped upstream, so we do not synthesize data.

"""

pools = {}

sub_all = df_like[df_like['smiles'] == linker]

for a in acts:

T,H,C,S = a

pool = sub_all[

(sub_all['temperature'] == T) &

(sub_all['time_h'] == H) &

(sub_all['concentration_M'] == C) &

(sub_all['solvent_DMF'] == S)

]

if not pool.empty:

pools[a] = pool.reset_index(drop=True)

def pull_fn(a, rng):

pool = pools.get(a)

if pool is None or len(pool) == 0:

return None

row = pool.iloc[int(rng.integers(0, len(pool)))]

return float(row['yield'])

return pull_fn

def fmt_action(a):

T,H,C,S = a

return f"T={T}°C, t={H}h, c={C:.2f} M, solvent={'DMF' if S==1 else 'H2O'}"

top_linkers

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

HTTPError Traceback (most recent call last)

Cell In[12], line 3

1 # Load full dataset

2 url = "https://raw.githubusercontent.com/zzhenglab/ai4chem/main/book/_data/mof_yield_dataset.csv"

----> 3 df_raw = pd.read_csv(url)

5 # Pick the 10 most frequent linkers so each has adequate coverage in the table

6 top_linkers = df_raw['smiles'].value_counts().head(10).index.tolist()

File ~\AppData\Local\Programs\Python\Python313\Lib\site-packages\pandas\io\parsers\readers.py:1026, in read_csv(filepath_or_buffer, sep, delimiter, header, names, index_col, usecols, dtype, engine, converters, true_values, false_values, skipinitialspace, skiprows, skipfooter, nrows, na_values, keep_default_na, na_filter, verbose, skip_blank_lines, parse_dates, infer_datetime_format, keep_date_col, date_parser, date_format, dayfirst, cache_dates, iterator, chunksize, compression, thousands, decimal, lineterminator, quotechar, quoting, doublequote, escapechar, comment, encoding, encoding_errors, dialect, on_bad_lines, delim_whitespace, low_memory, memory_map, float_precision, storage_options, dtype_backend)

1013 kwds_defaults = _refine_defaults_read(

1014 dialect,

1015 delimiter,

(...) 1022 dtype_backend=dtype_backend,

1023 )

1024 kwds.update(kwds_defaults)

-> 1026 return _read(filepath_or_buffer, kwds)

File ~\AppData\Local\Programs\Python\Python313\Lib\site-packages\pandas\io\parsers\readers.py:620, in _read(filepath_or_buffer, kwds)

617 _validate_names(kwds.get("names", None))

619 # Create the parser.

--> 620 parser = TextFileReader(filepath_or_buffer, **kwds)

622 if chunksize or iterator:

623 return parser

File ~\AppData\Local\Programs\Python\Python313\Lib\site-packages\pandas\io\parsers\readers.py:1620, in TextFileReader.__init__(self, f, engine, **kwds)

1617 self.options["has_index_names"] = kwds["has_index_names"]

1619 self.handles: IOHandles | None = None

-> 1620 self._engine = self._make_engine(f, self.engine)

File ~\AppData\Local\Programs\Python\Python313\Lib\site-packages\pandas\io\parsers\readers.py:1880, in TextFileReader._make_engine(self, f, engine)

1878 if "b" not in mode:

1879 mode += "b"

-> 1880 self.handles = get_handle(

1881 f,

1882 mode,

1883 encoding=self.options.get("encoding", None),

1884 compression=self.options.get("compression", None),

1885 memory_map=self.options.get("memory_map", False),

1886 is_text=is_text,

1887 errors=self.options.get("encoding_errors", "strict"),

1888 storage_options=self.options.get("storage_options", None),

1889 )

1890 assert self.handles is not None

1891 f = self.handles.handle

File ~\AppData\Local\Programs\Python\Python313\Lib\site-packages\pandas\io\common.py:728, in get_handle(path_or_buf, mode, encoding, compression, memory_map, is_text, errors, storage_options)

725 codecs.lookup_error(errors)

727 # open URLs

--> 728 ioargs = _get_filepath_or_buffer(

729 path_or_buf,

730 encoding=encoding,

731 compression=compression,

732 mode=mode,

733 storage_options=storage_options,

734 )

736 handle = ioargs.filepath_or_buffer

737 handles: list[BaseBuffer]

File ~\AppData\Local\Programs\Python\Python313\Lib\site-packages\pandas\io\common.py:384, in _get_filepath_or_buffer(filepath_or_buffer, encoding, compression, mode, storage_options)

382 # assuming storage_options is to be interpreted as headers

383 req_info = urllib.request.Request(filepath_or_buffer, headers=storage_options)

--> 384 with urlopen(req_info) as req:

385 content_encoding = req.headers.get("Content-Encoding", None)

386 if content_encoding == "gzip":

387 # Override compression based on Content-Encoding header

File ~\AppData\Local\Programs\Python\Python313\Lib\site-packages\pandas\io\common.py:289, in urlopen(*args, **kwargs)

283 """

284 Lazy-import wrapper for stdlib urlopen, as that imports a big chunk of

285 the stdlib.

286 """

287 import urllib.request

--> 289 return urllib.request.urlopen(*args, **kwargs)

File ~\AppData\Local\Programs\Python\Python313\Lib\urllib\request.py:189, in urlopen(url, data, timeout, context)

187 else:

188 opener = _opener

--> 189 return opener.open(url, data, timeout)

File ~\AppData\Local\Programs\Python\Python313\Lib\urllib\request.py:495, in OpenerDirector.open(self, fullurl, data, timeout)

493 for processor in self.process_response.get(protocol, []):

494 meth = getattr(processor, meth_name)

--> 495 response = meth(req, response)

497 return response

File ~\AppData\Local\Programs\Python\Python313\Lib\urllib\request.py:604, in HTTPErrorProcessor.http_response(self, request, response)

601 # According to RFC 2616, "2xx" code indicates that the client's

602 # request was successfully received, understood, and accepted.

603 if not (200 <= code < 300):

--> 604 response = self.parent.error(

605 'http', request, response, code, msg, hdrs)

607 return response

File ~\AppData\Local\Programs\Python\Python313\Lib\urllib\request.py:533, in OpenerDirector.error(self, proto, *args)

531 if http_err:

532 args = (dict, 'default', 'http_error_default') + orig_args

--> 533 return self._call_chain(*args)

File ~\AppData\Local\Programs\Python\Python313\Lib\urllib\request.py:466, in OpenerDirector._call_chain(self, chain, kind, meth_name, *args)

464 for handler in handlers:

465 func = getattr(handler, meth_name)

--> 466 result = func(*args)

467 if result is not None:

468 return result

File ~\AppData\Local\Programs\Python\Python313\Lib\urllib\request.py:613, in HTTPDefaultErrorHandler.http_error_default(self, req, fp, code, msg, hdrs)

612 def http_error_default(self, req, fp, code, msg, hdrs):

--> 613 raise HTTPError(req.full_url, code, msg, hdrs, fp)

HTTPError: HTTP Error 404: Not Found

5.2 Bandit framing and algorithms#

We treat each unique recipe as an arm and the yield as the reward. Rewards are bounded in [0, 1], which suits UCB1 on sample means.

For Thompson sampling we use a Beta posterior heuristic that accumulates alpha plus equal to yield and beta plus equal to 1 minus yield. This gives a simple way to sample optimistic beliefs for continuous bounded outcomes without converting to binary success. We also include ε greedy on the mean yield for a familiar baseline.

All algorithms run per linker so each linker gets a focused search over the actions that actually appear in the data.

# Section 2: Bandit agents for bounded rewards in [0,1]

def run_eps_mean_linker(df_like, linker, Tsteps=400, eps=0.1, seed=0):

acts = linker_actions(df_like, linker)

if len(acts) == 0:

return dict(avg=np.array([]), n=np.array([]), s=np.array([]), best=None, acts=[])

rng = np.random.default_rng(seed)

K = len(acts)

n = np.zeros(K, int) # pulls

s = np.zeros(K, float) # sum of yields

avg = []; total = 0.0

pull = make_pull_yield(df_like, linker, acts)

for t in range(1, Tsteps+1):

if rng.random() < eps:

a = int(rng.integers(0, K))

else:

est = s / np.maximum(1, n)

m = est.max(); ties = np.flatnonzero(np.isclose(est, m))

a = int(rng.choice(ties))

r = pull(acts[a], rng)

if r is None:

continue

n[a]+=1; s[a]+=r; total+=r

avg.append(total/t)

if n.sum()==0:

return dict(avg=np.array([]), n=n, s=s, best=None, acts=acts)

best = int(np.argmax(s/np.maximum(1,n)))

return dict(avg=np.asarray(avg), n=n, s=s, best=best, acts=acts)

def run_ucb1_mean_linker(df_like, linker, Tsteps=400, seed=0):

acts = linker_actions(df_like, linker)

if len(acts) == 0:

return dict(avg=np.array([]), n=np.array([]), s=np.array([]), best=None, acts=[])

rng = np.random.default_rng(seed)

K = len(acts)

n = np.zeros(K, int); s = np.zeros(K, float)

avg = []; total = 0.0

pull = make_pull_yield(df_like, linker, acts)

# small warm start to avoid zero-division

tried = 0

for a in range(min(K, 10)):

r = pull(acts[a], rng)

if r is None:

continue

n[a]+=1; s[a]+=r; total+=r; tried += 1

avg.append(total/tried)

for t in range(tried+1, Tsteps+1):

est = s/np.maximum(1,n)

bonus = np.sqrt(2.0*np.log(max(2, t))/np.maximum(1,n))

a = int(np.argmax(est + bonus))

r = pull(acts[a], rng)

if r is None:

continue

n[a]+=1; s[a]+=r; total+=r

avg.append(total/(len(avg)+1))

if n.sum()==0:

return dict(avg=np.array([]), n=n, s=s, best=None, acts=acts)

best = int(np.argmax(s/np.maximum(1,n)))

return dict(avg=np.asarray(avg), n=n, s=s, best=best, acts=acts)

def run_thompson_beta_linker(df_like, linker, Tsteps=400, seed=0):

"""

Thompson with a Beta posterior heuristic for bounded yields.

alpha += yield, beta += 1 - yield.

"""

acts = linker_actions(df_like, linker)

if len(acts) == 0:

return dict(avg=np.array([]), n=np.array([]), s=np.array([]), best=None, acts=[])

rng = np.random.default_rng(seed)

K = len(acts)

alpha = np.ones(K); beta = np.ones(K)

n = np.zeros(K, int); s = np.zeros(K, float)

avg = []; total = 0.0

pull = make_pull_yield(df_like, linker, acts)

for t in range(1, Tsteps+1):

samples = rng.beta(alpha, beta)

a = int(np.argmax(samples))

r = pull(acts[a], rng)

if r is None:

continue

n[a]+=1; s[a]+=r; total+=r

alpha[a] += r

beta[a] += (1.0 - r)

avg.append(total/t)

if n.sum()==0:

return dict(avg=np.array([]), n=n, s=s, best=None, acts=acts)

best = int(np.argmax(s/np.maximum(1,n)))

return dict(avg=np.asarray(avg), n=n, s=s, best=best, acts=acts)

def summarize_agent(linker, name, out):

best = out["best"]; acts = out["acts"]

if best is None or len(acts) == 0:

return dict(linker=linker, agent=name, recipe="NA", pulls=0, mean_yield=np.nan)

n, s = out["n"], out["s"]

return dict(

linker=linker, agent=name,

recipe=fmt_action(acts[best]),

pulls=int(n[best]),

mean_yield=float(s[best]/max(1,n[best]))

)

5.3 Running the agents and building a compact report#

We now run ε greedy, UCB1, and Thompson Beta for each of the 10 linkers. Each agent interacts with a simulator that returns yields for recipes that are actually in the table for that linker.

We then summarize the best recipe per agent by its mean yield and also produce one recommended recipe per linker by taking the top mean yield across agents. This gives a short list of general conditions to try first in the lab for each linker.

# Section 3: Execute agents and summarize best recipes per linker

results = []

curves = []

for linker in top_linkers:

eps = run_eps_mean_linker (df_raw, linker, Tsteps=50, eps=0.1, seed=42)

ucb = run_ucb1_mean_linker (df_raw, linker, Tsteps=50, seed=42)

ts = run_thompson_beta_linker(df_raw, linker, Tsteps=50, seed=42)

results.extend([

summarize_agent(linker, "eps_greedy", eps),

summarize_agent(linker, "ucb1", ucb),

summarize_agent(linker, "thompson_beta", ts),

])

curves.append((linker, eps.get("avg", np.array([])), ucb.get("avg", np.array([])), ts.get("avg", np.array([]))))

summary_df = pd.DataFrame(results).sort_values(["linker","mean_yield"], ascending=[True, False]).reset_index(drop=True)

print("Per-linker best by agent (first 12 rows):")

summary_df.head(12)

best_by_linker = (

summary_df

.groupby("linker", as_index=False)

.first()[["linker","agent","recipe","pulls","mean_yield"]]

)

print("\nOne recommended recipe per linker by highest mean yield across agents:")

best_by_linker

5.4 Interpreting the results and tracking learning#

The table lists a best recipe per agent for each linker together with the number of pulls used to estimate its mean yield. If a best recipe shows very few pulls you can increase the step budget or run another pass to confirm stability. Learning curves help you see whether the agent is still exploring or has stabilized on a high yielding recipe. Consistent upward trends suggest the action set has a clear winner for that linker. Flat or noisy curves suggest multiple near ties or limited coverage in the dataset for that linker.

5.5 General synthesis condition works best across all linkers#

Finally, instead of looking at per-linker optima, we can also look at if there is a a single “general” synthesis condition across the 10 linkers.

Note

This computes the “general condition” that gives the highest average yield across multiple linkers. It first finds recipes appearing for most linkers, computes their true mean yield per linker from the dataset, then averages those means. The result lists a single synthesis condition that is empirically best overall, along with its average, median, and range of yields across linkers.

Results: === General synthesis condition (best average yield across linkers) === recipe T=130°C, t=60h, c=0.25 M, solvent=DMF coverage 10 mean_yield_all 0.73 median_yield 0.855 min_yield 0.23 max_yield 0.99

6. Glossary#

- Agent #

The decision maker that picks the next experiment.

- Environment #

The lab or simulator returning outcomes.

- Policy #

Mapping from states to actions.

- Q value #

Expected return from a state-action pair.

- Return #

Discounted sum of future rewards.

- Epsilon greedy #

Random with probability epsilon, else greedy.

- UCB1 #

Bonus for uncertainty to balance exploration.

- Thompson sampling #

Posterior sampling strategy.

- On policy #

Learn about the policy you execute.

7. In-class activity#

Q1#

Now it’s time to review the detailed code for the three demo games. Identify where the reward score is defined, and modify it in the code to observe how the behavior changes.

You can also adjust the design of the games. For example, change 0 and 1 in demo 3 to see how this influences the agent in finding the optimal strategy.